FROM BIOMORPHIC TO GEOMETRIC, 1962-1969

December 4, 2025 - February 13, 2026

Installation Views | Essay | For availability and pricing, call 212-581-1657.

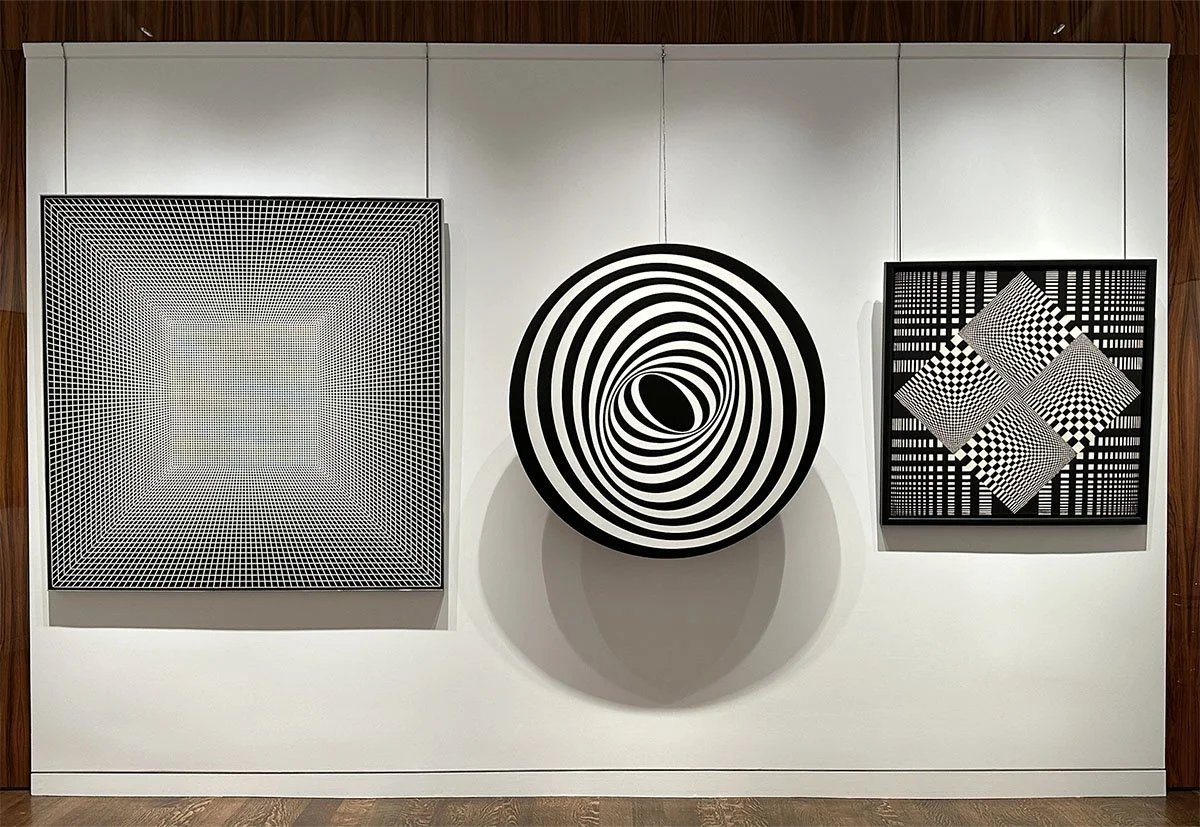

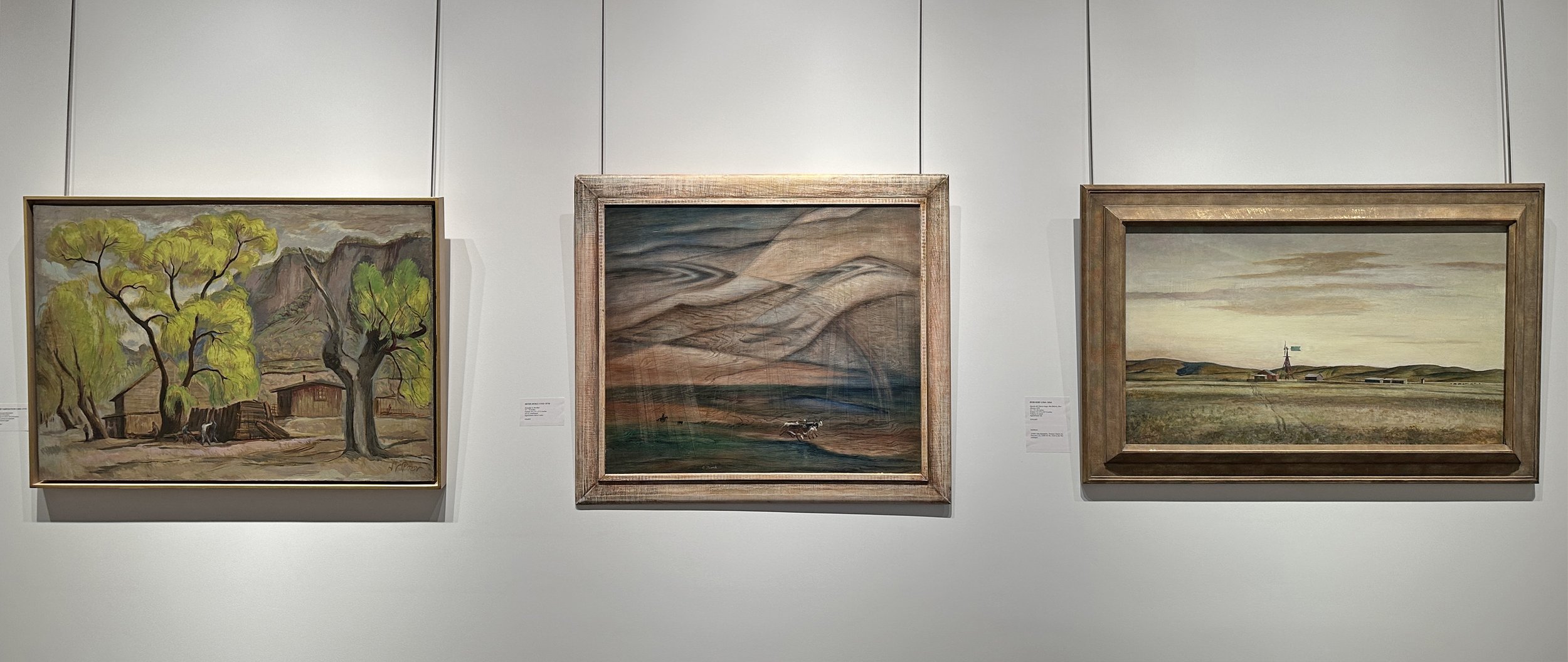

Installation Views

Essay by Emily Lenz

Our exhibition at the gallery complements Paul Reed's major retrospective at the Oklahoma City Museum of Art curated by David Gariff, senior lecturer at the National Gallery of Art. The retrospective includes over one hundred paintings, sculptures, and works on paper drawn from the Oklahoma City Museum of Art's holdings, several DC museums, and private collections across the country. The retrospective runs from November 22, 2025 to April 12, 2026.

The Oklahoma City Museum of Art has a long history with the Washington Color School artists, which includes Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Gene Davis, Thomas Downing, Howard Mehring, and Paul Reed. In 1968 the museum purchased the entire collection of the Washington Gallery of Modern Art, founded in 1961 to increase attention given to contemporary art in the nation's capital. Facing closure due to poor finances, the Washington Gallery had to settle its debts to merge with the Corcoran Gallery of Art and have its building serve as an annex. J. Robert Porter, a museum board trustee born and raised in Oklahoma City, coordinated the sale of 154 works to the then Oklahoma Art Center. The history of the Washington Gallery of Modern Art and how its collection came to Oklahoma was covered in the 2007 exhibition catalogue Breaking the Mold: Selections from the Washington Gallery of Modern Art, 1961-1968 and further discussed in the new Paul Reed exhibition catalogue.

In 1965, the Washington Gallery of Modern Art’s director Gerald Nordland organized the landmark exhibition Washington Color Painters featuring Paul Reed, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Gene Davis, Thomas Downing, and Howard Mehring. These DC-based artists used recently developed acrylic paints directly on unprimed canvas, embedding or staining the color into the painting’s surface. This approach created a new sense of color that glowed and seemed to float. The Washington Color Painters exhibition traveled across the country bringing the group national recognition. The venues included: the University of Texas Art Galleries (now the Blanton Museum) in Austin, the University of California in Santa Barbara, the Rose Art Gallery at Brandeis University, and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. The six Washington Color painters first formed connections in the 1950s through DC art organizations. Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis both taught at the Washington Workshop for the Arts in 1952. Howard Mehring and Thomas Downing studied with Noland at Catholic University in 1953. Gene Davis and Paul Reed were childhood friends and met regularly at the Phillips Collection beginning in 1952. The six Washington artists became aware of each other’s works in the mid-1950s with their inclusion in exhibitions at Barnett-Aden Gallery, associated with Howard University, and later exhibitions at Jefferson Place Gallery, associated with American University. Noland first exhibited his Target paintings at Jefferson Place Gallery in 1958.

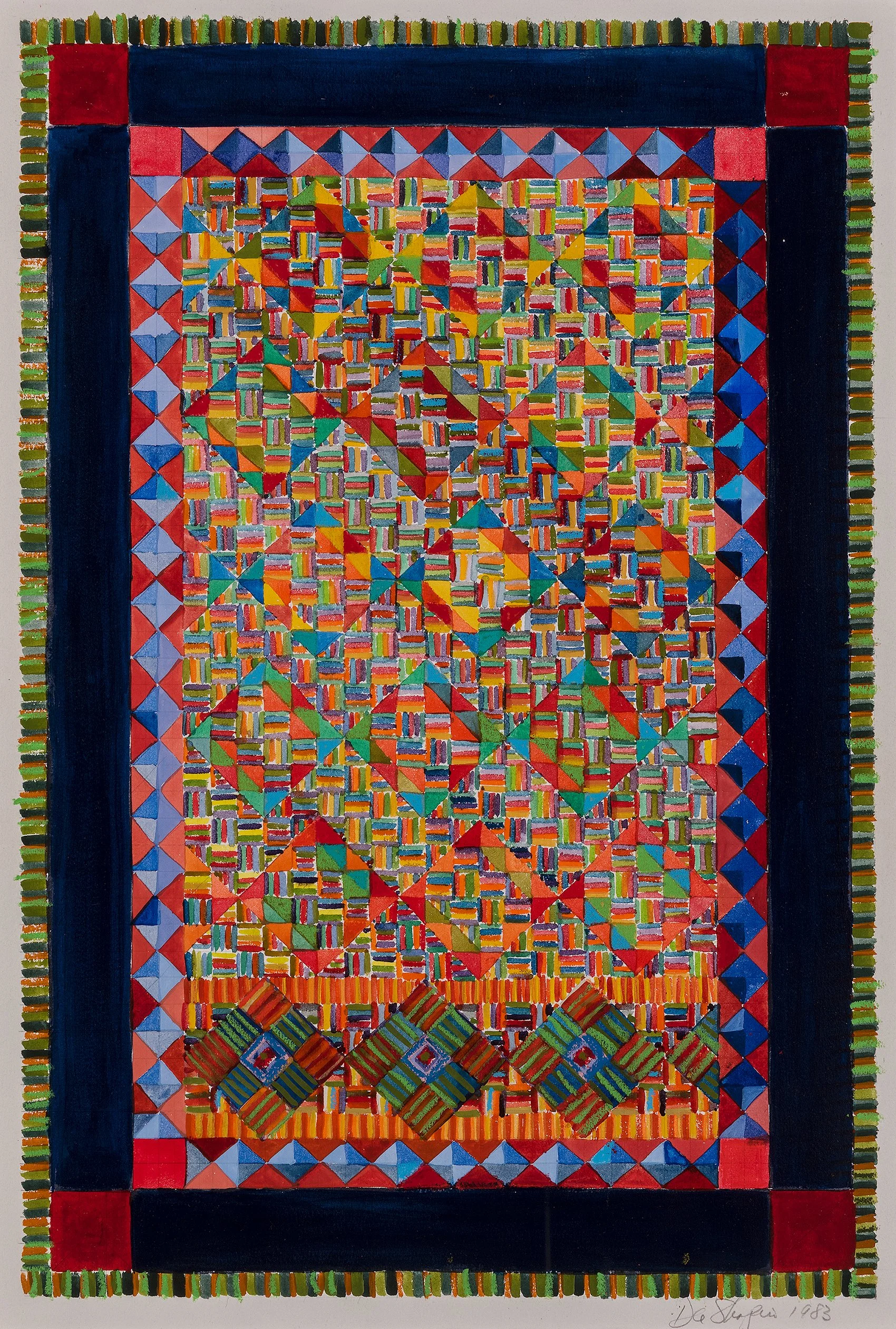

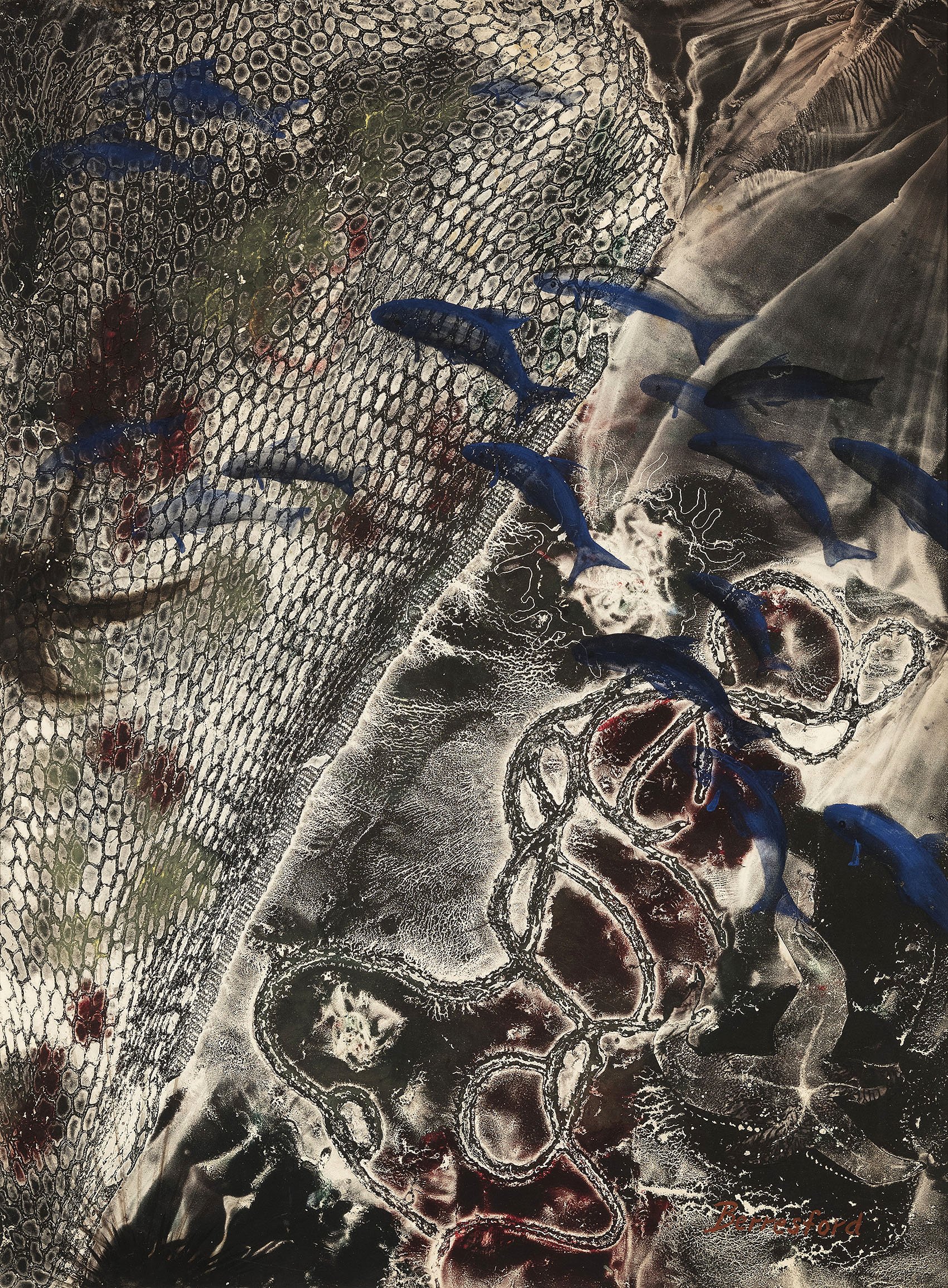

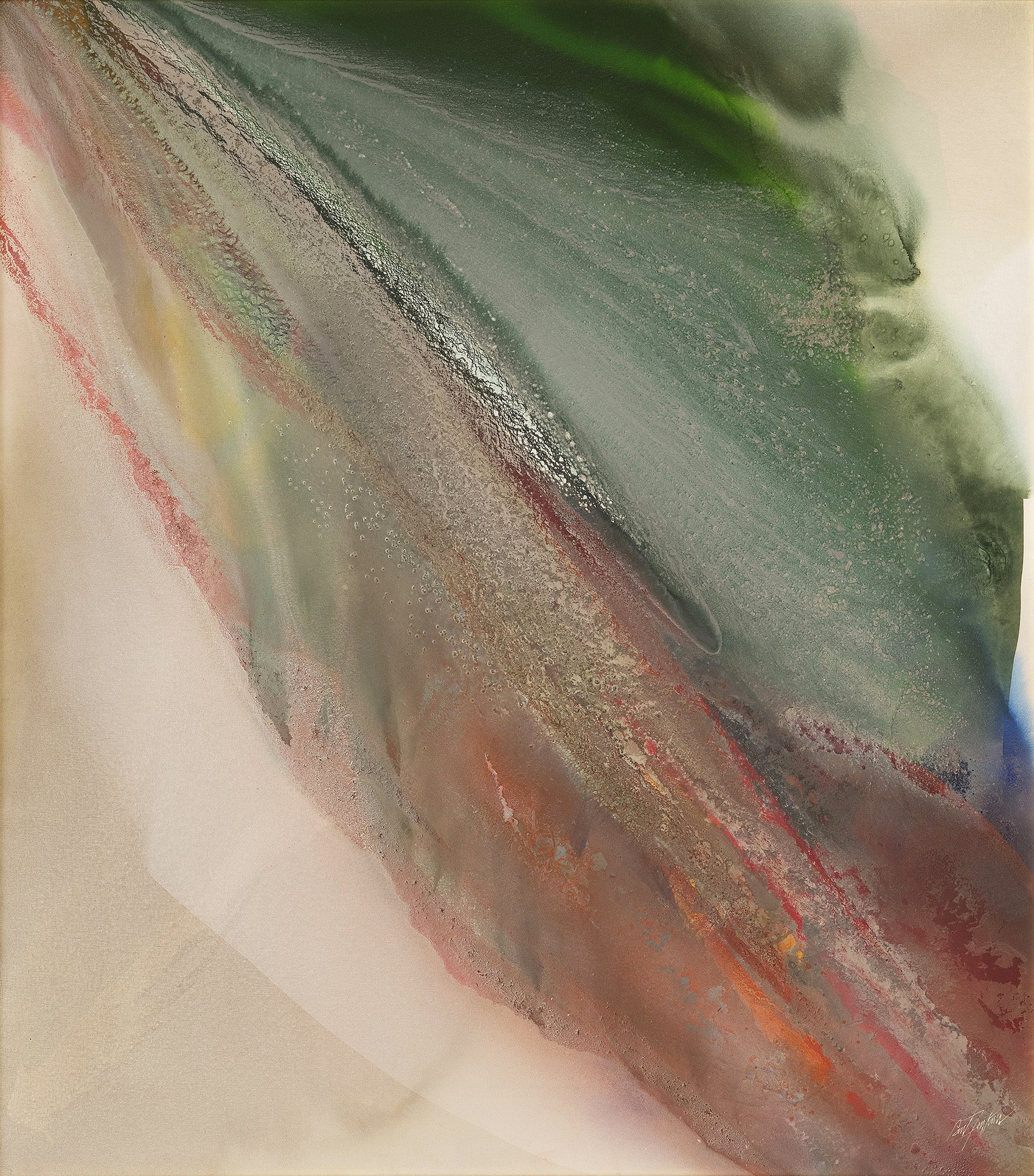

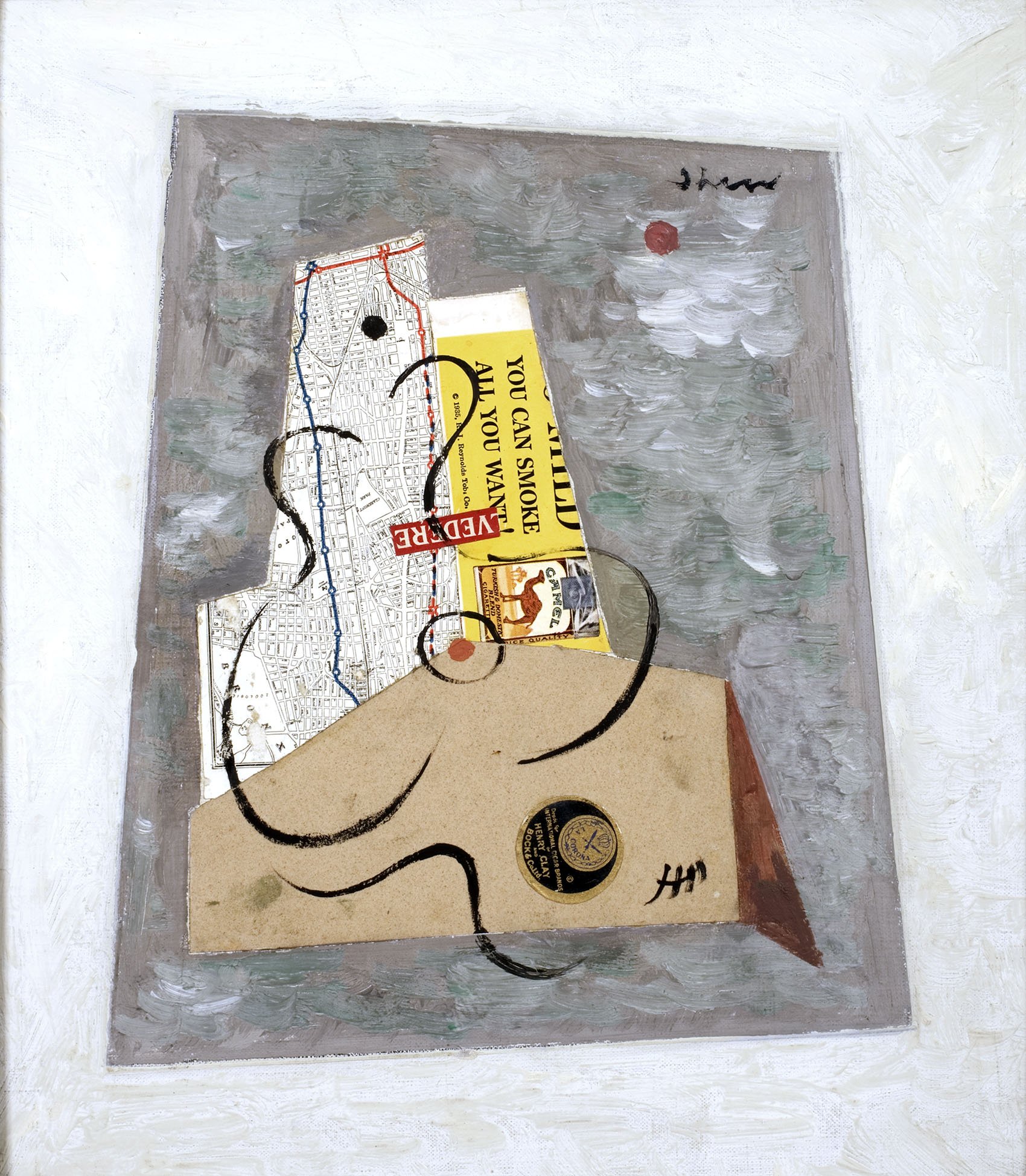

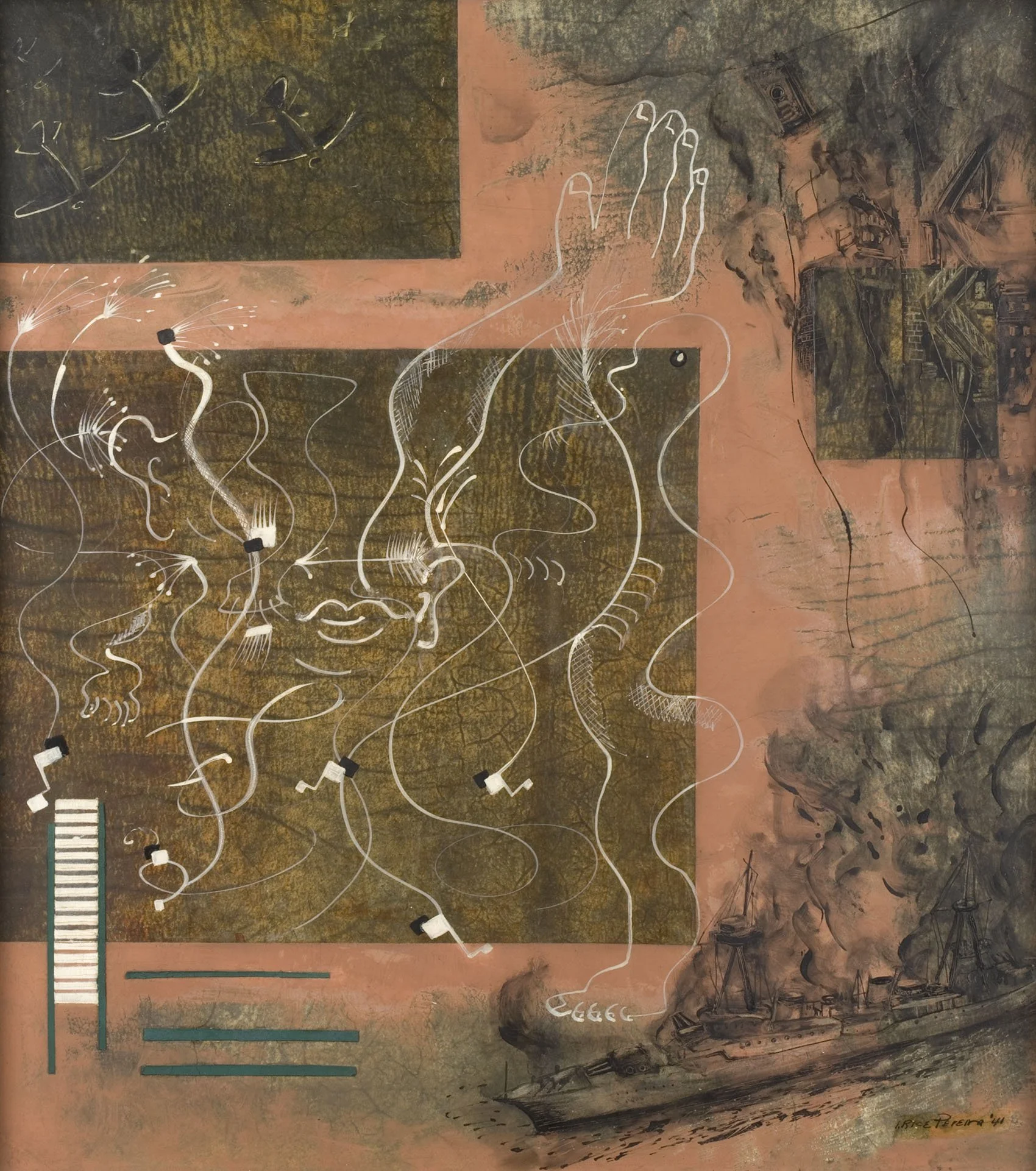

Our exhibition Paul Reed (1919-2015): From Biomorphic to Geometric includes 18 works executed from 1962 to 1969. The selection aims to show Paul Reed’s exploration of color and transparency to achieve movement in evolving series. Reed began with biomorphic shapes in circular motion (1962 to 1964), then he explored geometric structures (1964 to 1965) that crystallize into grids (1966), which then twist and stretch into shaped canvases (1967-1970). Reed worked experimentally through each series to investigate the properties of color as he moved from biomorphic to geometric paintings in the Sixties. Trained as a graphic designer, Reed settled on his compositions through calculated steps. First, he drew shapes until he settled on a form that would hold his envisioned color exercise. Second, he worked in collage and colored tissue paper to see how the color and transparency might work. Third, he applied the form to canvas, now intuitively seeing where he could take the color. Once he achieved the most complex and sophisticated colors for that form, the series was over. Reed said all his ideas were built on lessons learned from previous forms.

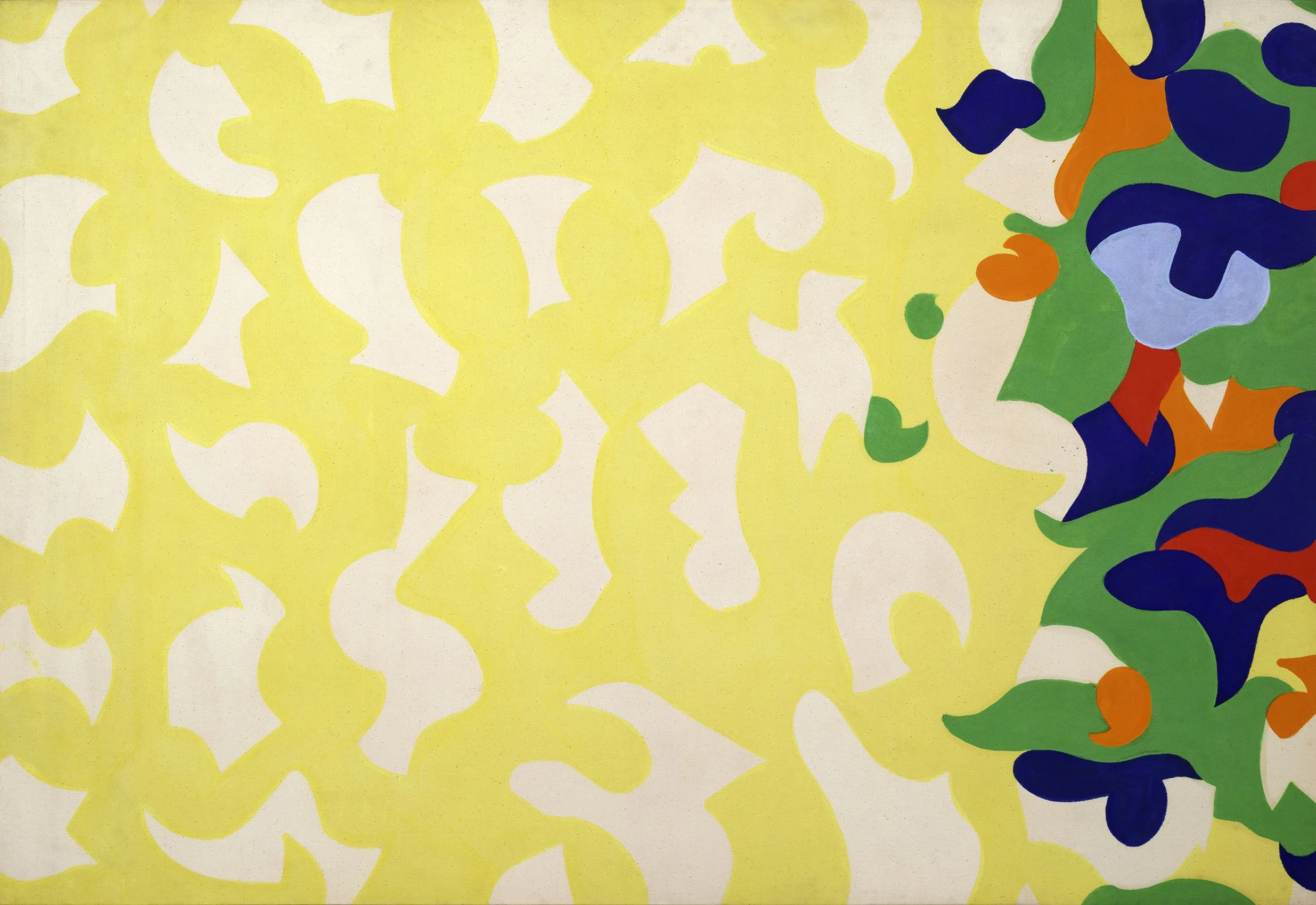

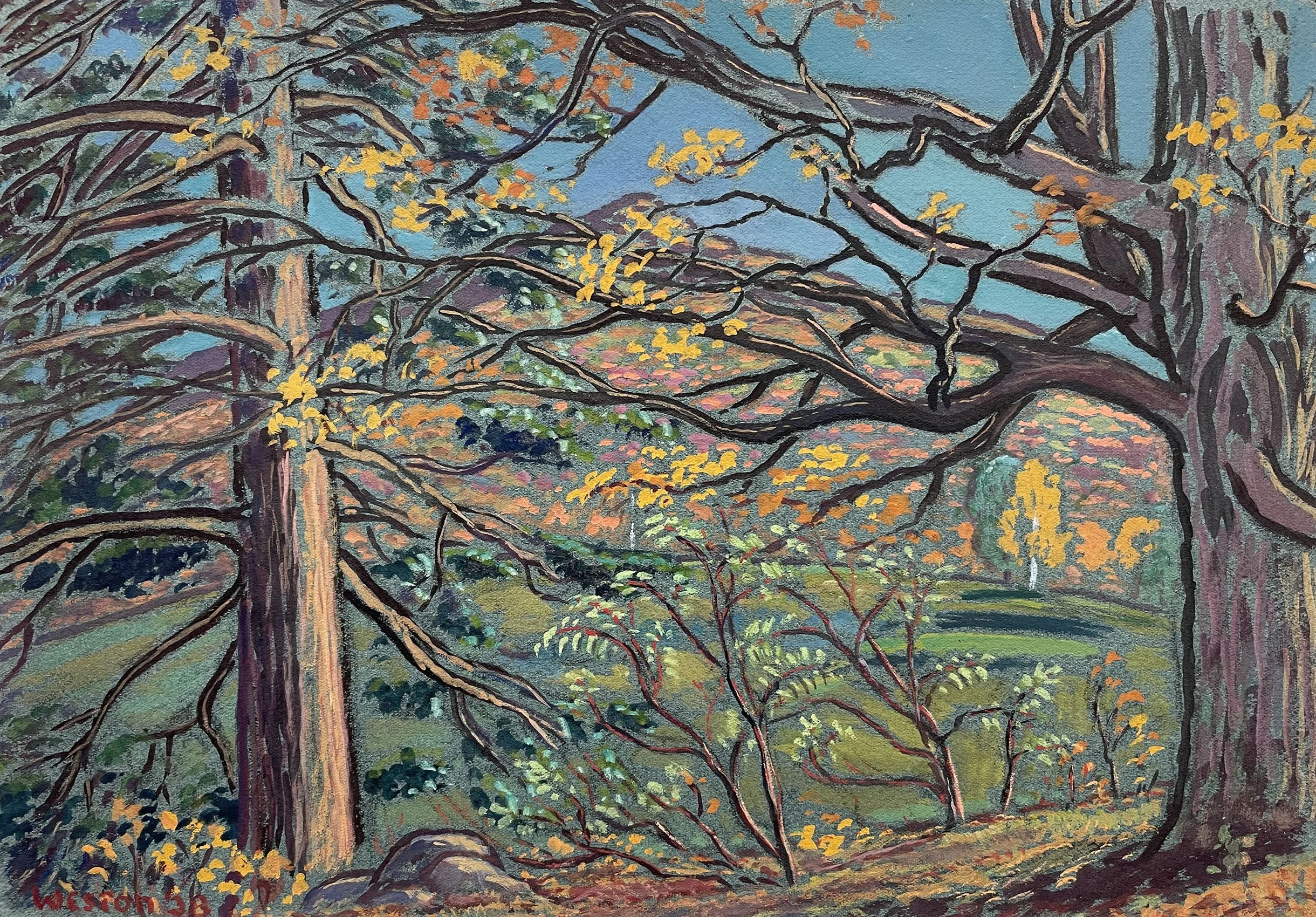

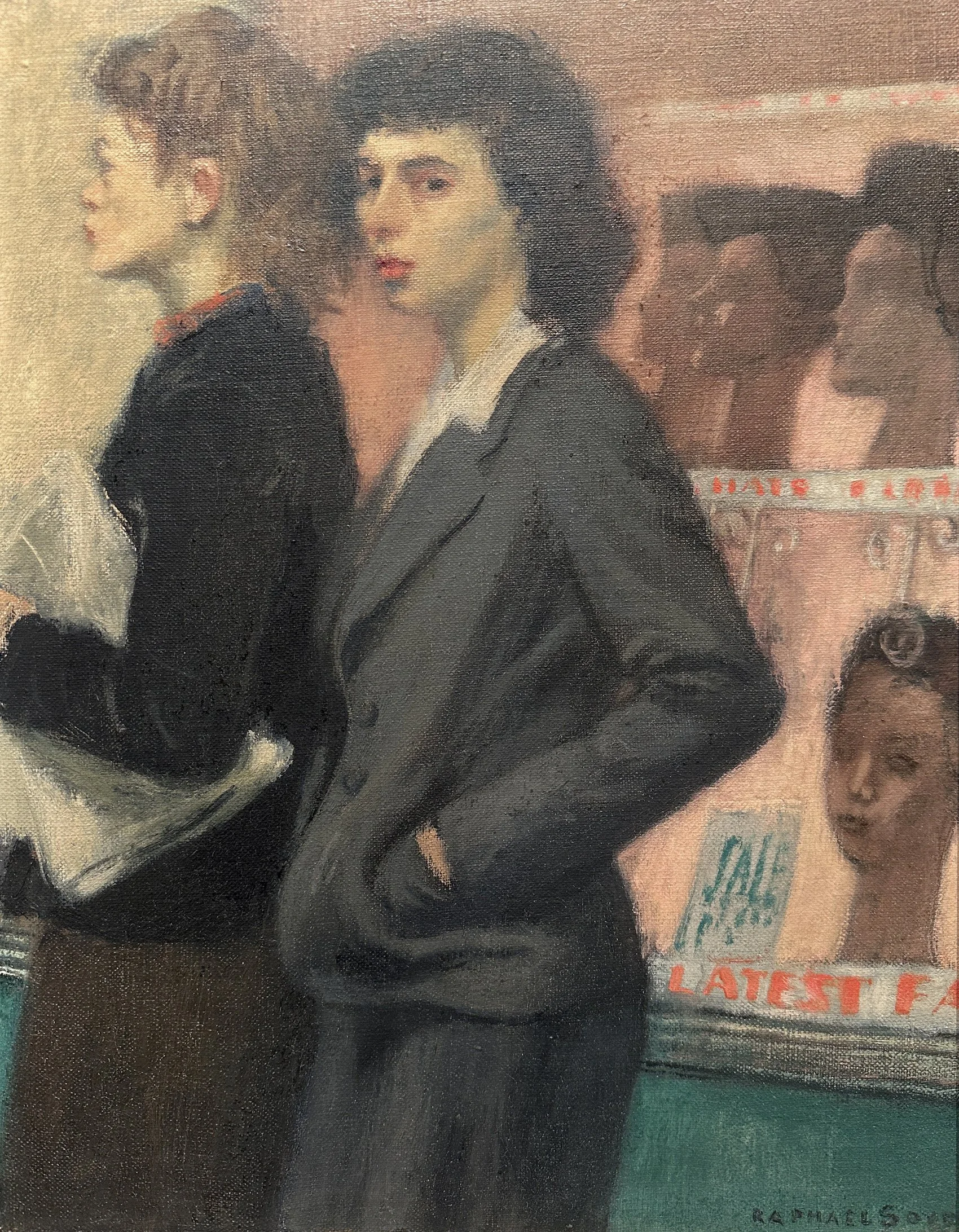

#12, 1962

Paul Reed found his own style in 1962 using interlocking forms based loosely on a grid. He first used these shapes in all-over compositions then moved to centered compositions on a field of raw canvas. In #12, 1962 in our exhibition, raw canvas shapes float above a yellow field with a mass of colorful forms to one side. There is a strong sense of Matisse’s late cut-out works in the shapes and movement. Comparisons to Matisse are felt in many of Reed’s colorful biomorphic works. Matisse’s cut-outs were the subject of a 1961 exhibition at MoMA in New York. The Reed family gifted a significant body of work to Oklahoma City Museum of Art after the museum pushed to include their Reed painting in the 2016 loan exhibition Matisse in His Time, drawn from the collection of the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

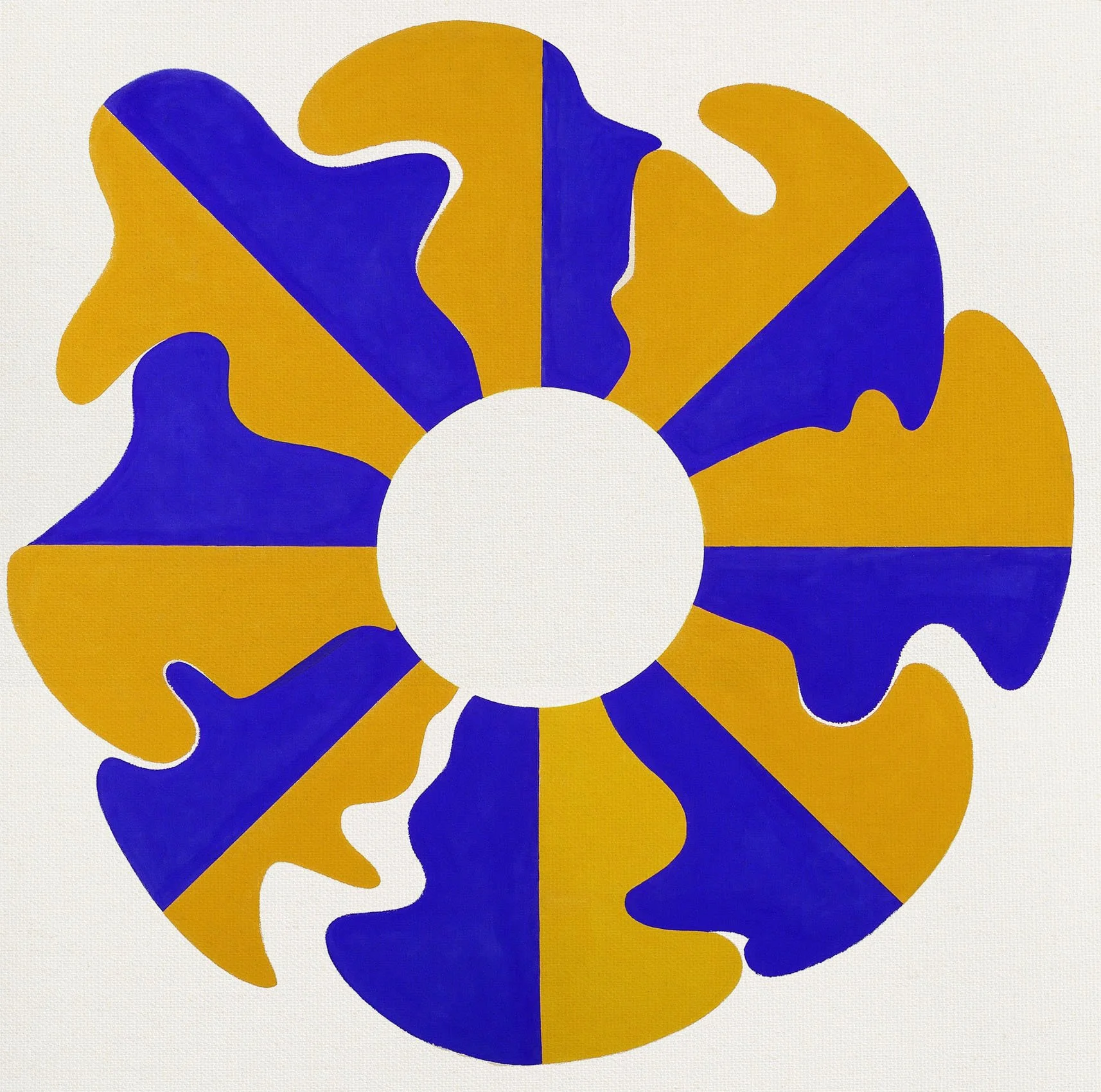

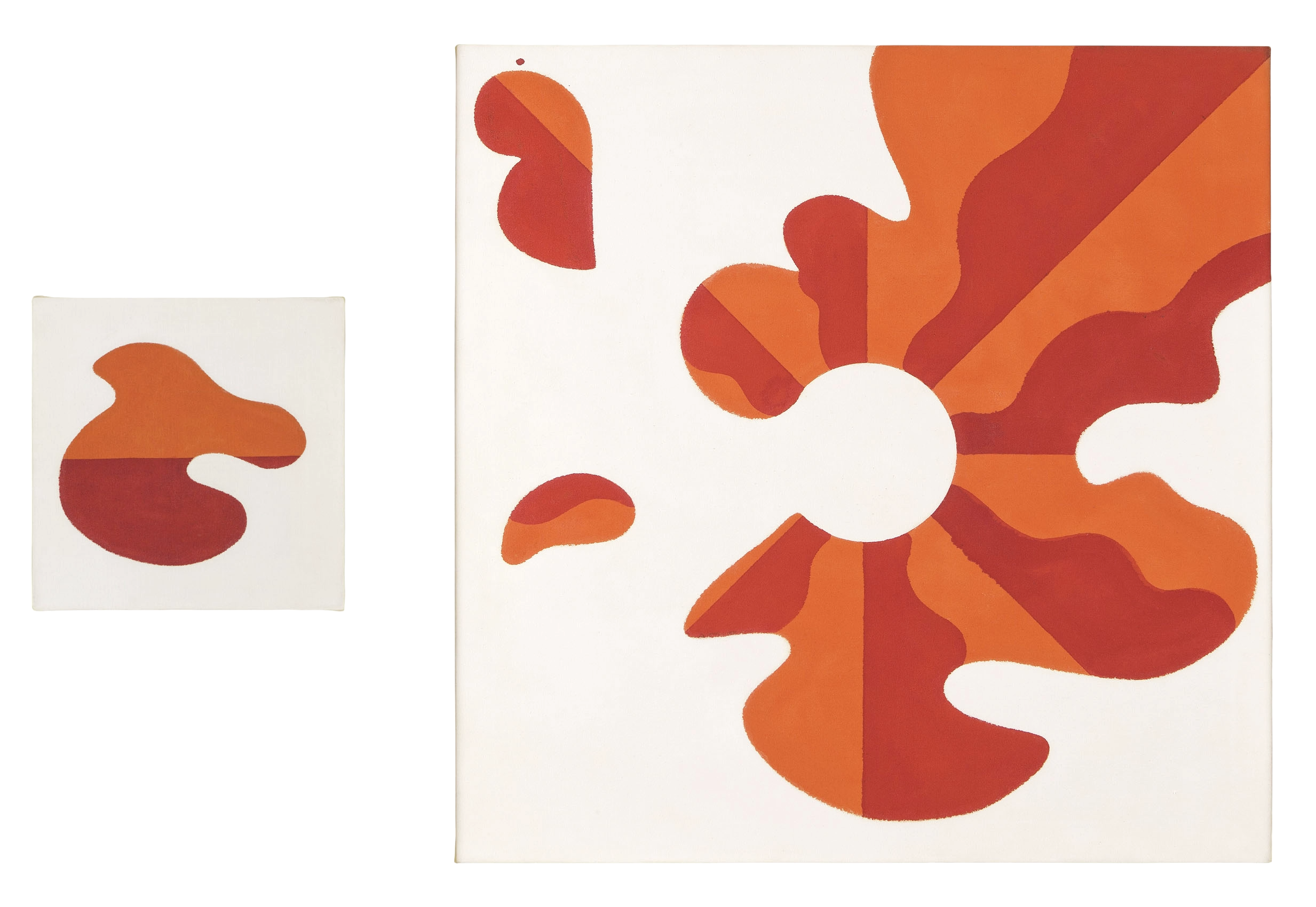

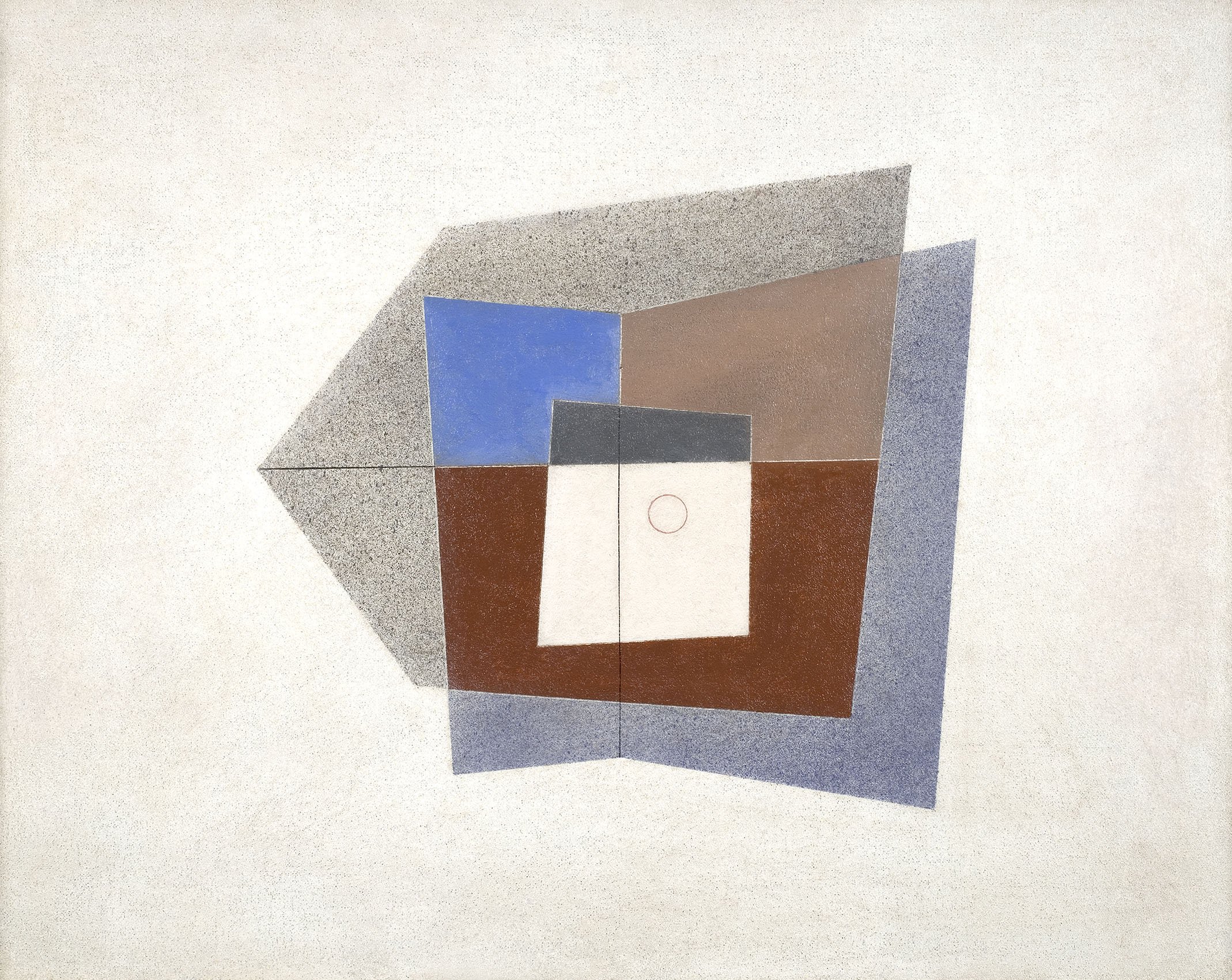

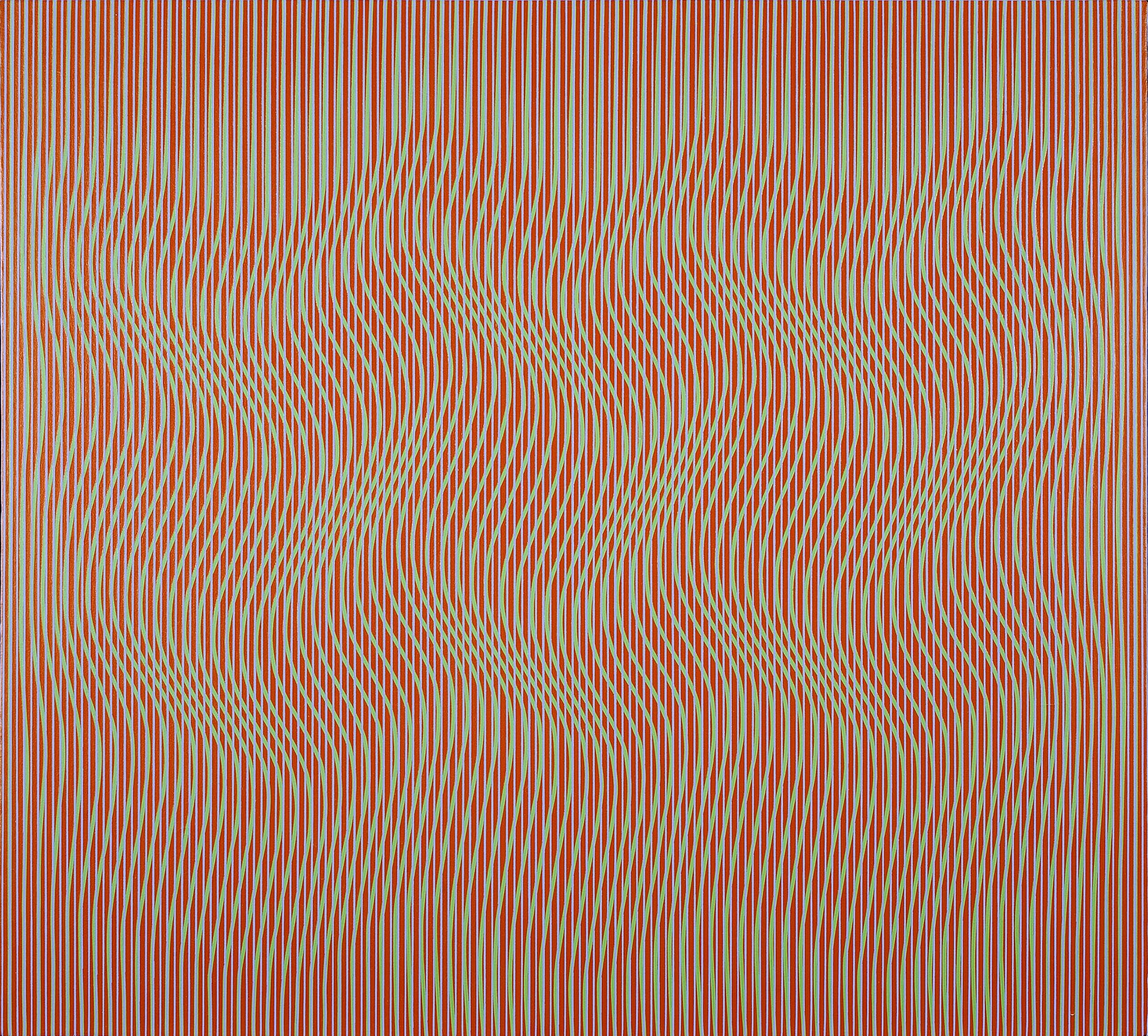

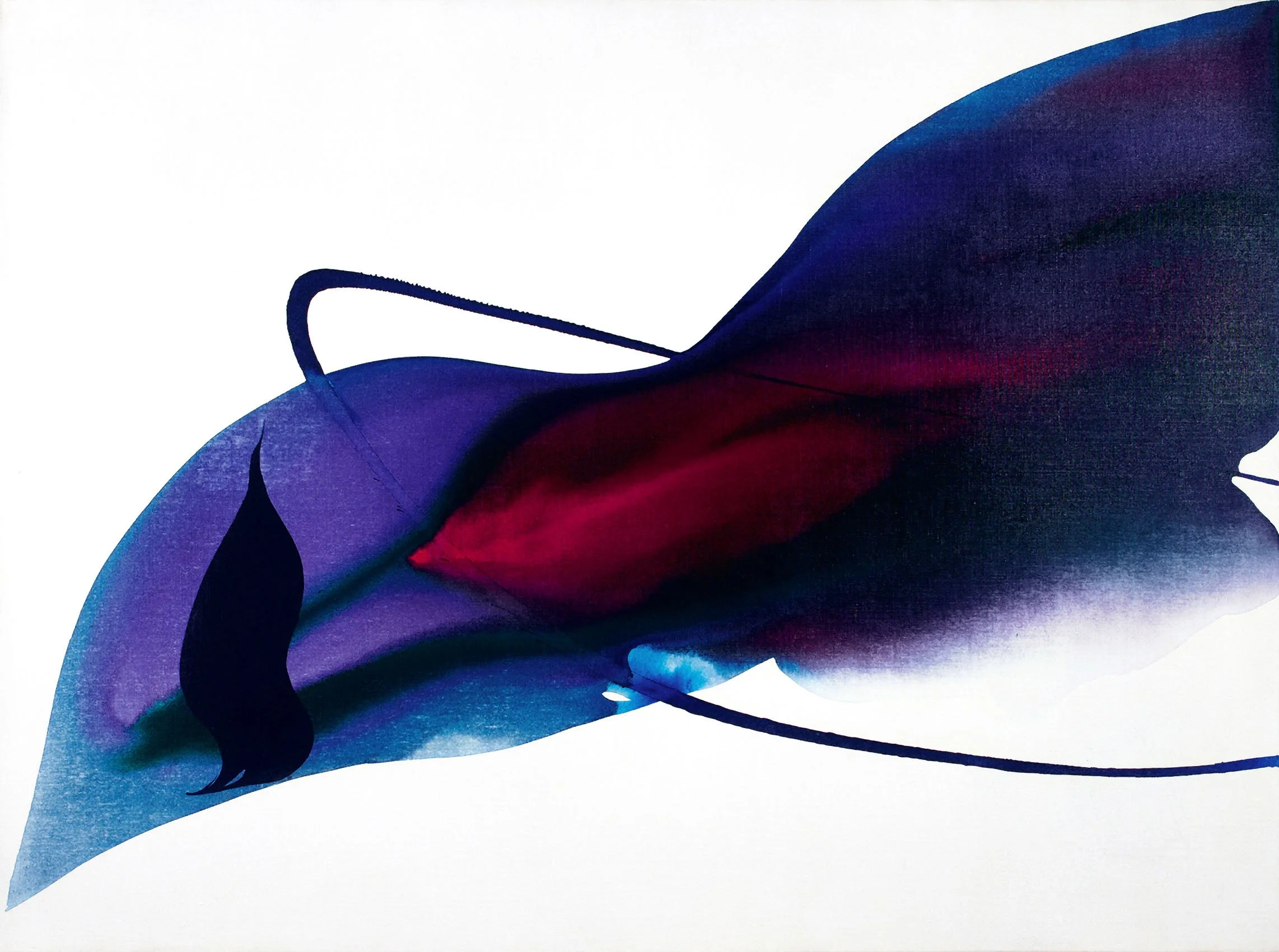

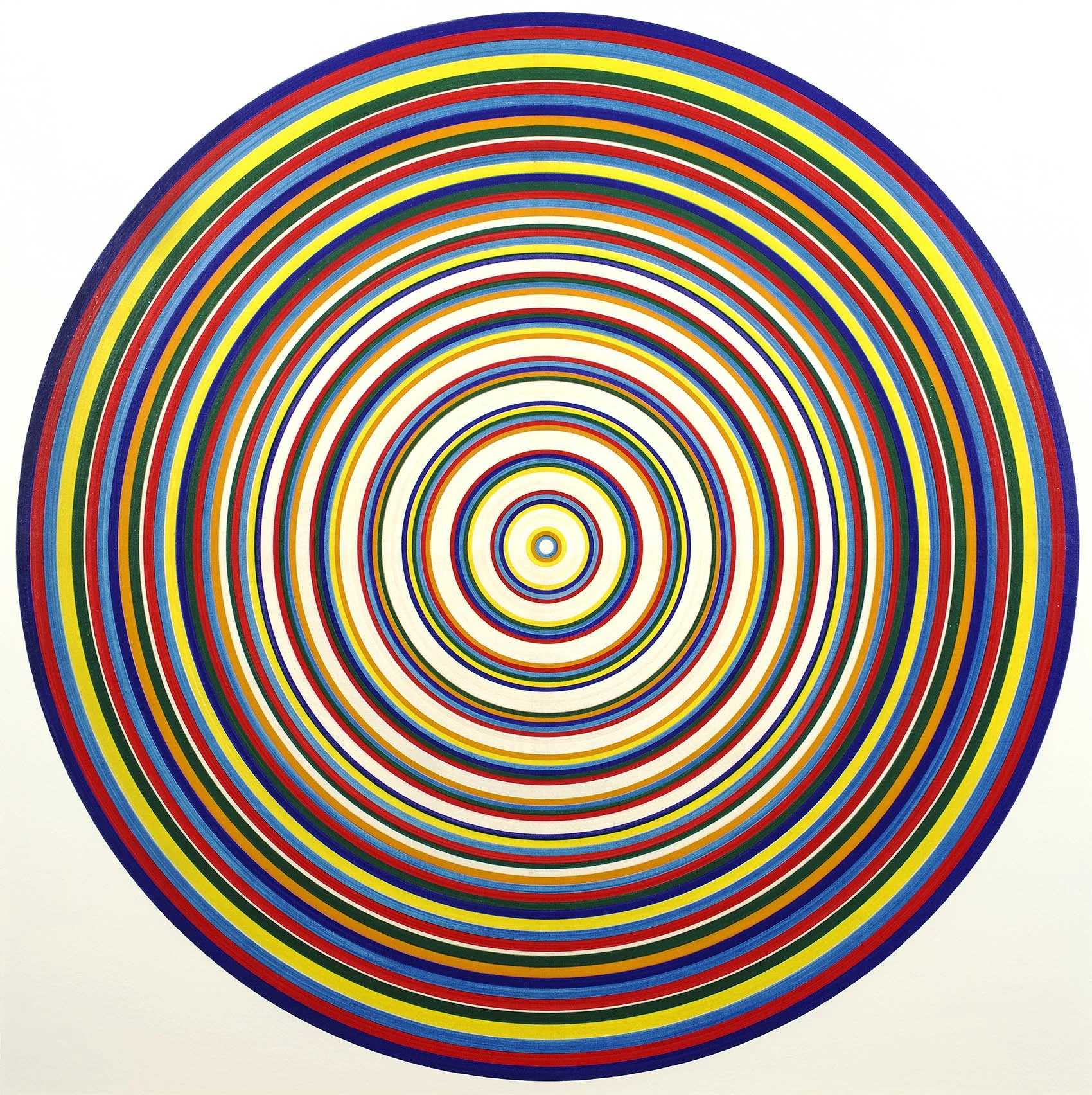

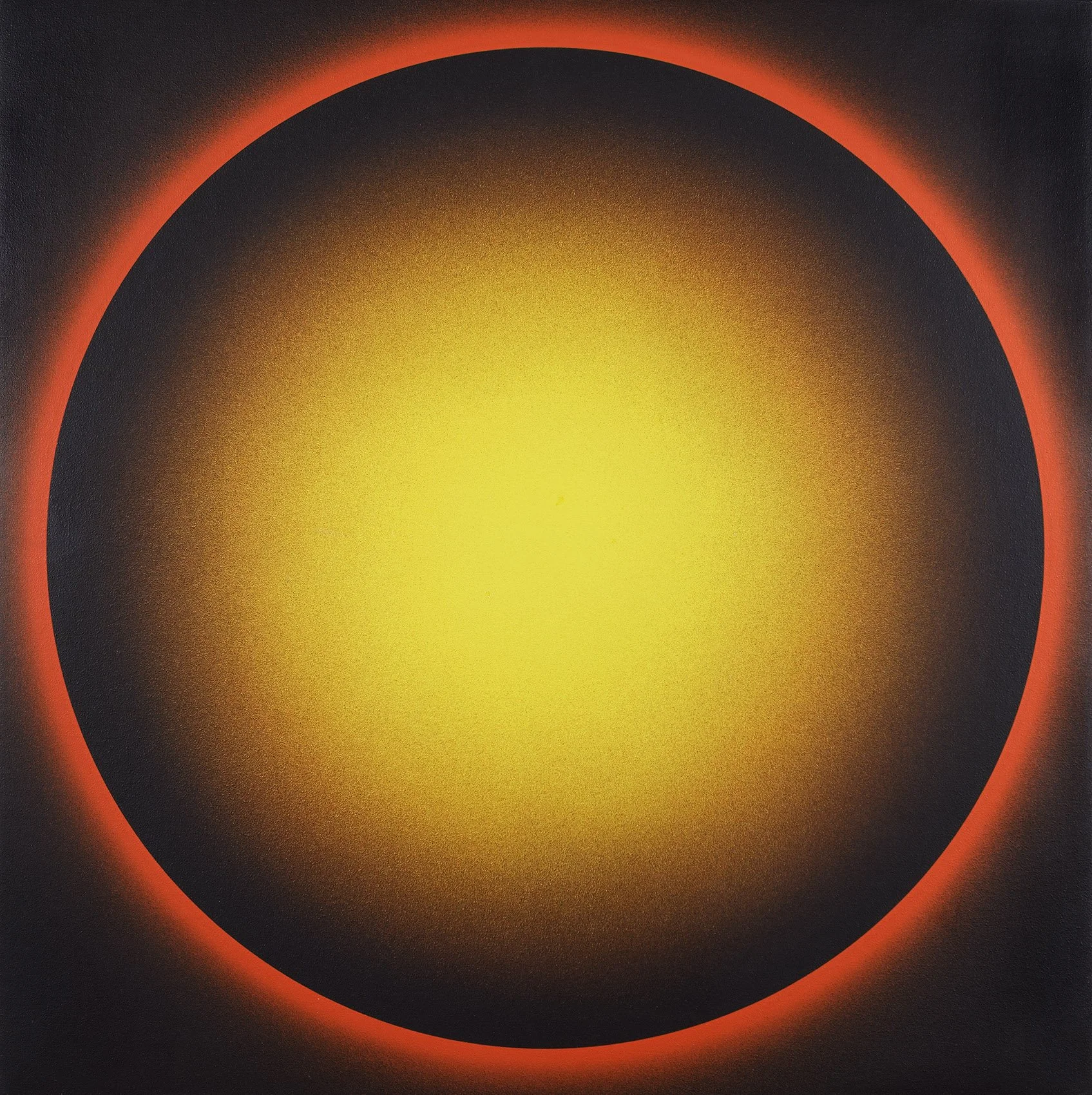

Another important artist to Paul Reed was Josef Albers and his theory of simultaneous contrast in color theory. The Washington Gallery of Modern Art noted the importance of Albers on young American artists with the exhibition Albers: The American Years in 1965. To create a new type of movement, Reed applied Albers’ color theory to curved forms to pair the energy of color contrasts with the energy of a curve. In #20C, 1963, alternating red and orange forms revolve around a raw canvas center. Three small offshoots emphasize the movement. This feeling of centrifugal force led Reed to the Satellite Paintings, such as #13, where a single form breaks out of the central painting to become a smaller canvas nearby. In the introductory text for Reed's first solo exhibition in DC at the Adams-Morgan Gallery in January of 1963, fellow artist Howard Mehring wrote, "He has chosen a curved energized shape as a vehicle for color, a shape which itself seems to express the properties of color vibration and pulsation….They move and play freely or converge on a center gently touching and overlapping. We catch their joy and their sense of play, their friendliness."

Satellite Painting #13, 1963

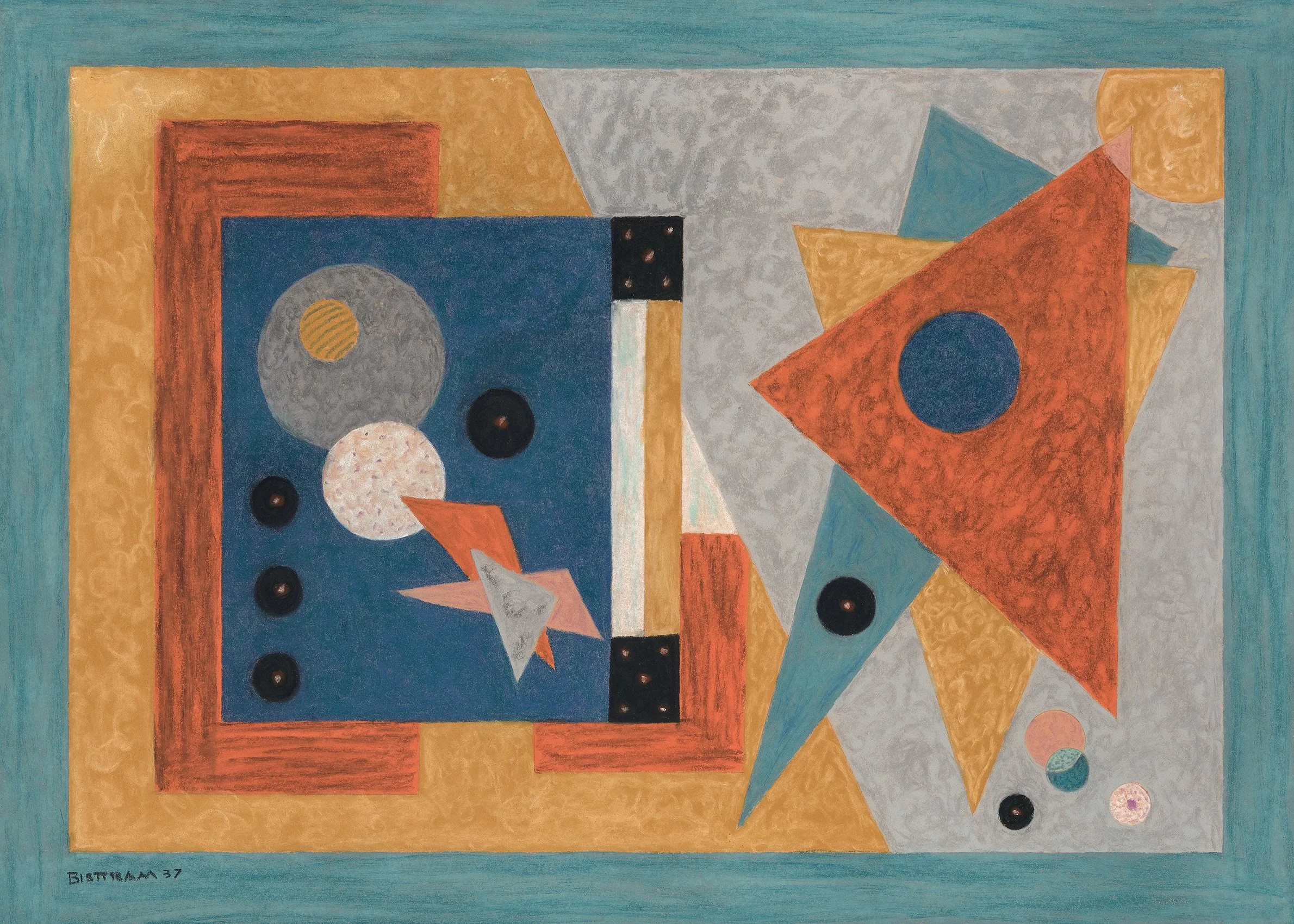

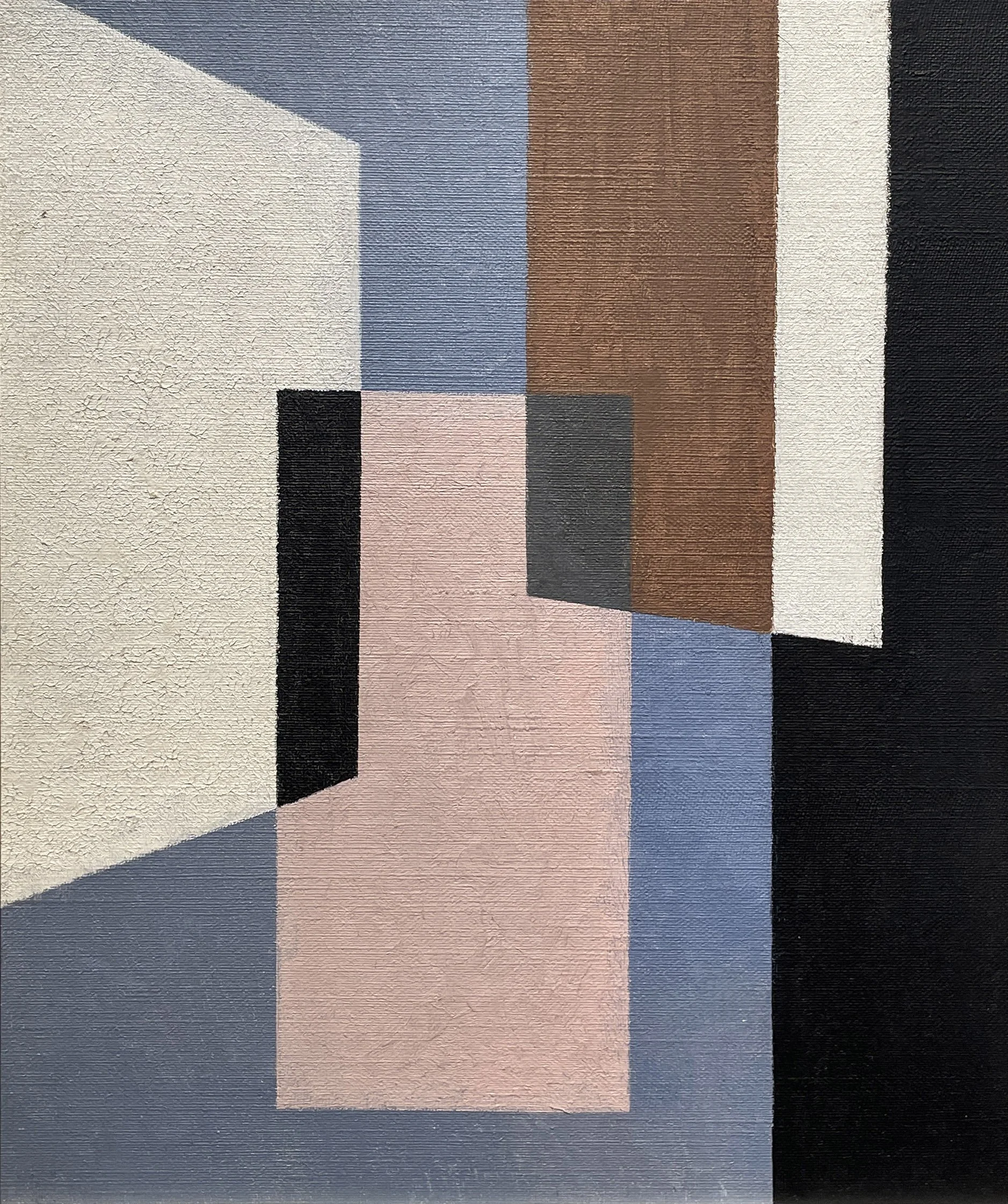

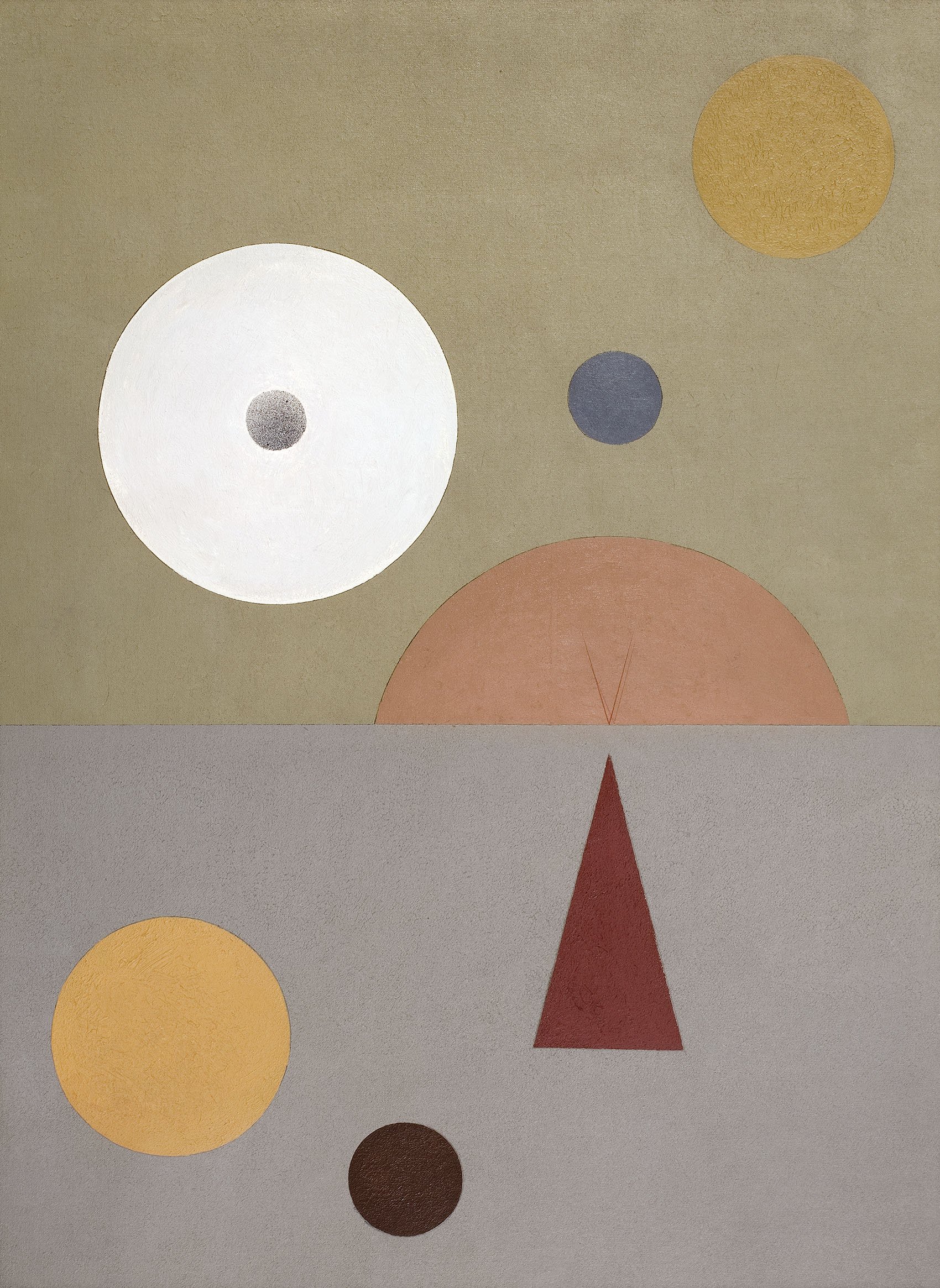

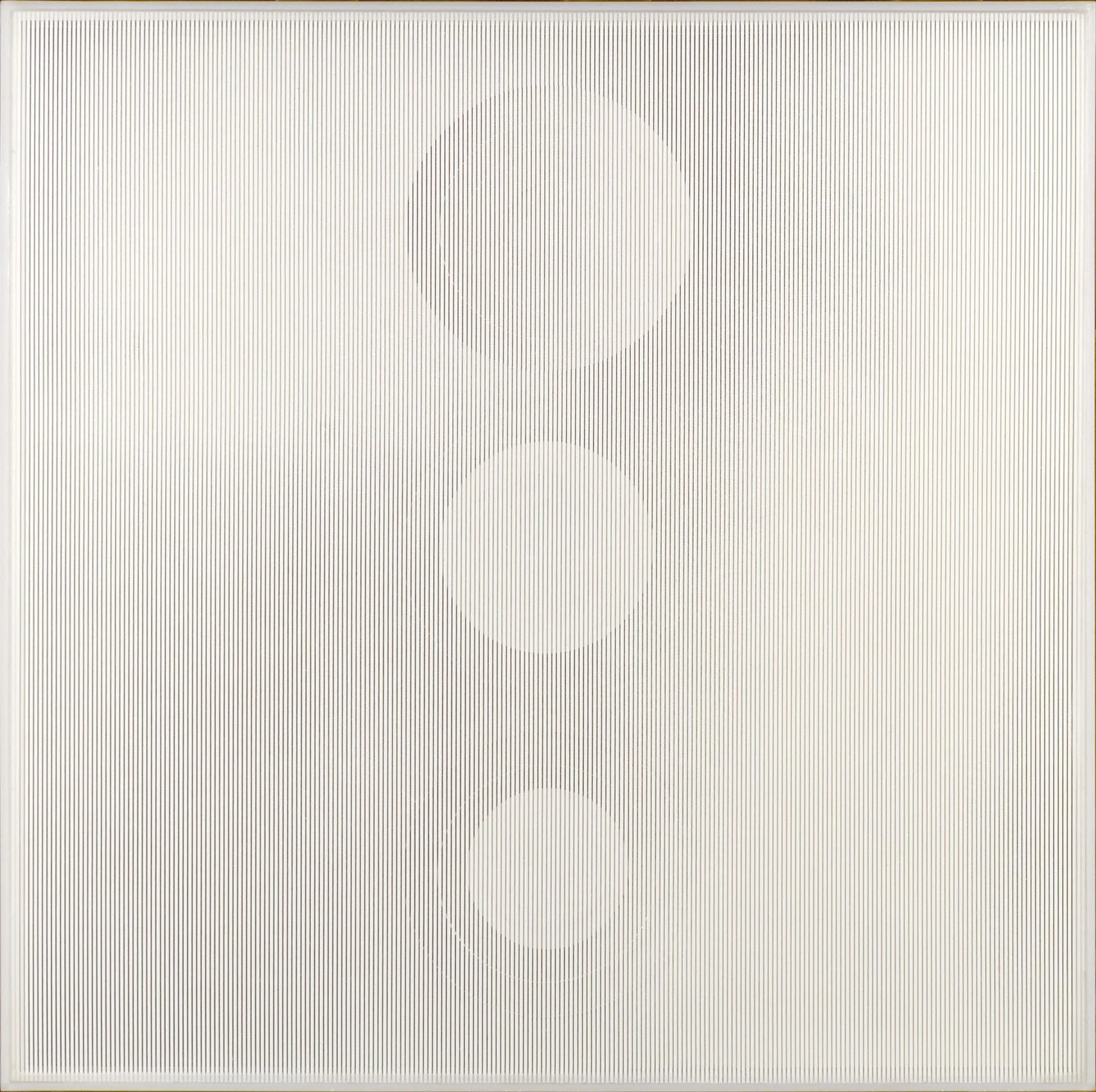

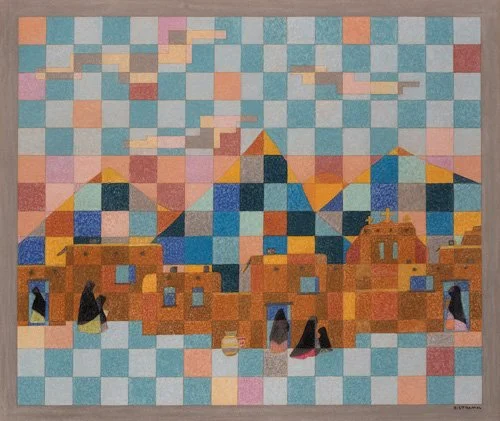

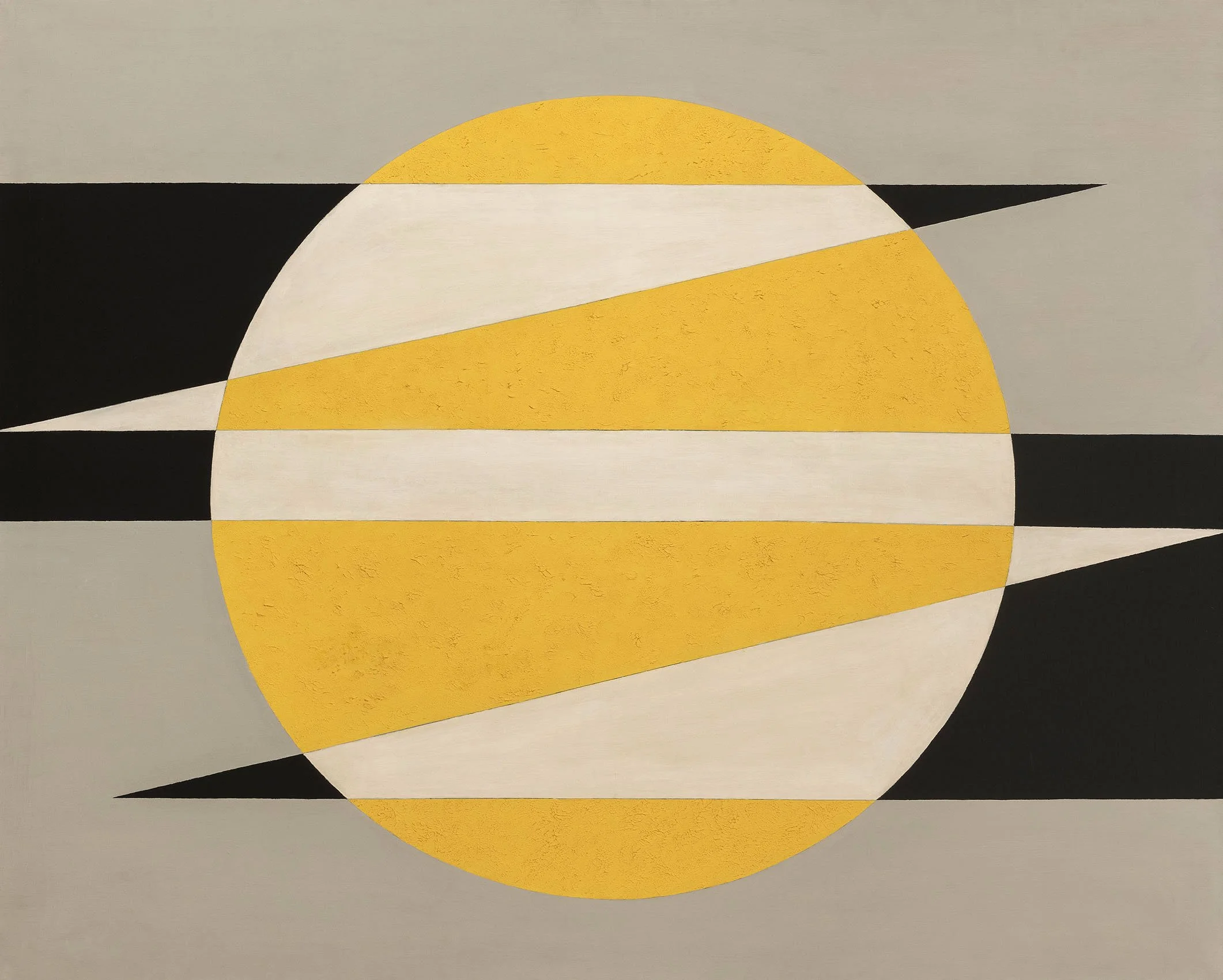

In 1964 Paul Reed introduced more geometry into his paintings by adding triangles of colors to the corners of his compositions. This is seen in #25C in which a flower-like form of eight mauve petals on a yellow field are anchored by orange and blue corners that add an ambiguous reading of figure and ground. 1965 marked Reed’s pivot from biomorphic to geometric. He simplified his compositions by keeping the triangles at the corners but turning the central arrangement of multiple shapes into a single circle which he called Disk Paintings. In these paintings, he could investigate the transparent qualities of water-based acrylic paints in overlapping some colors (the background and triangles) and not others (the central circle). #14B in our exhibition was owned by Phillips Collection curator Jim McLaughlin (1909–1982). The Corcoran Gallery of Art had an exhibition of the Disk Paintings in 1966.

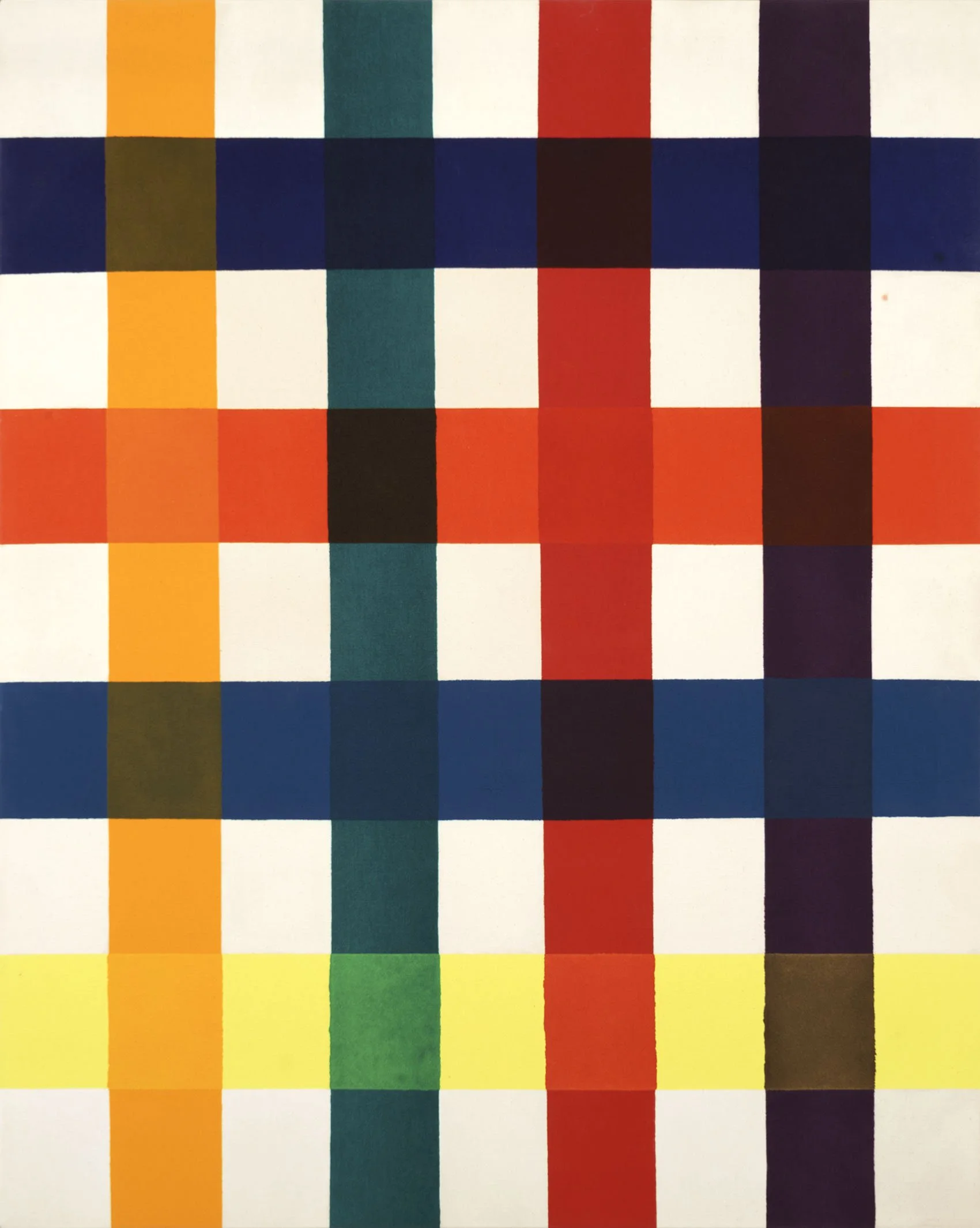

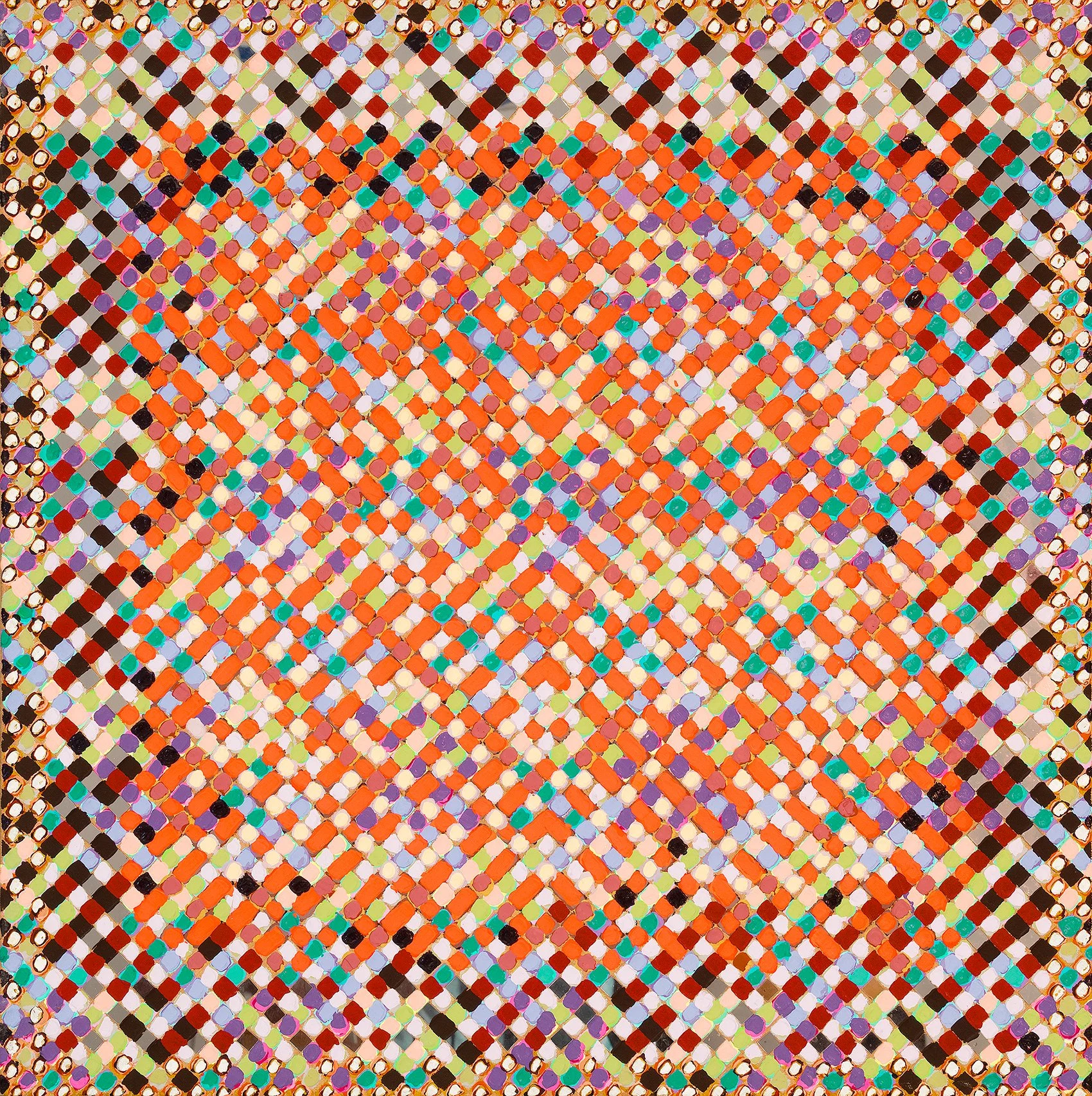

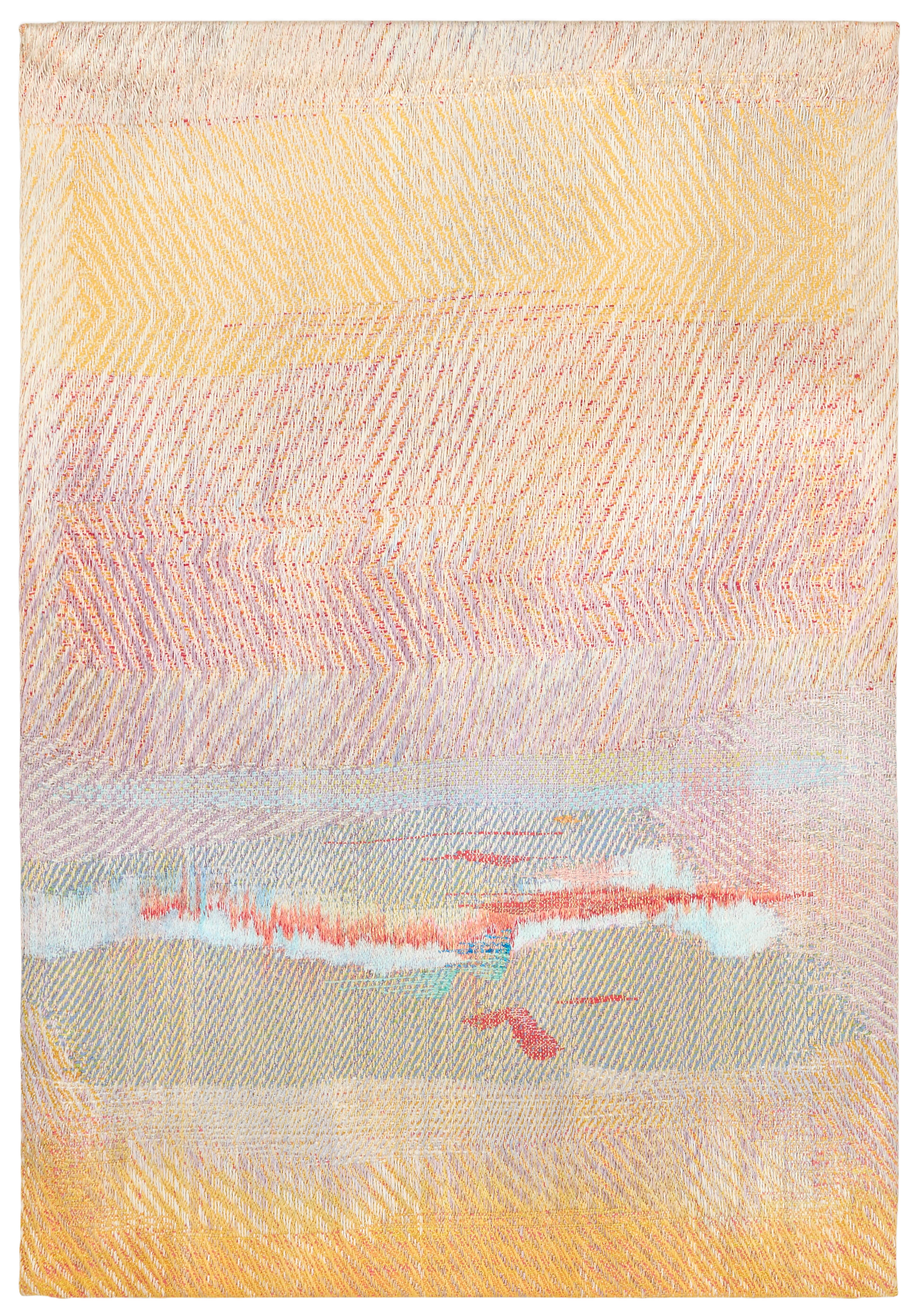

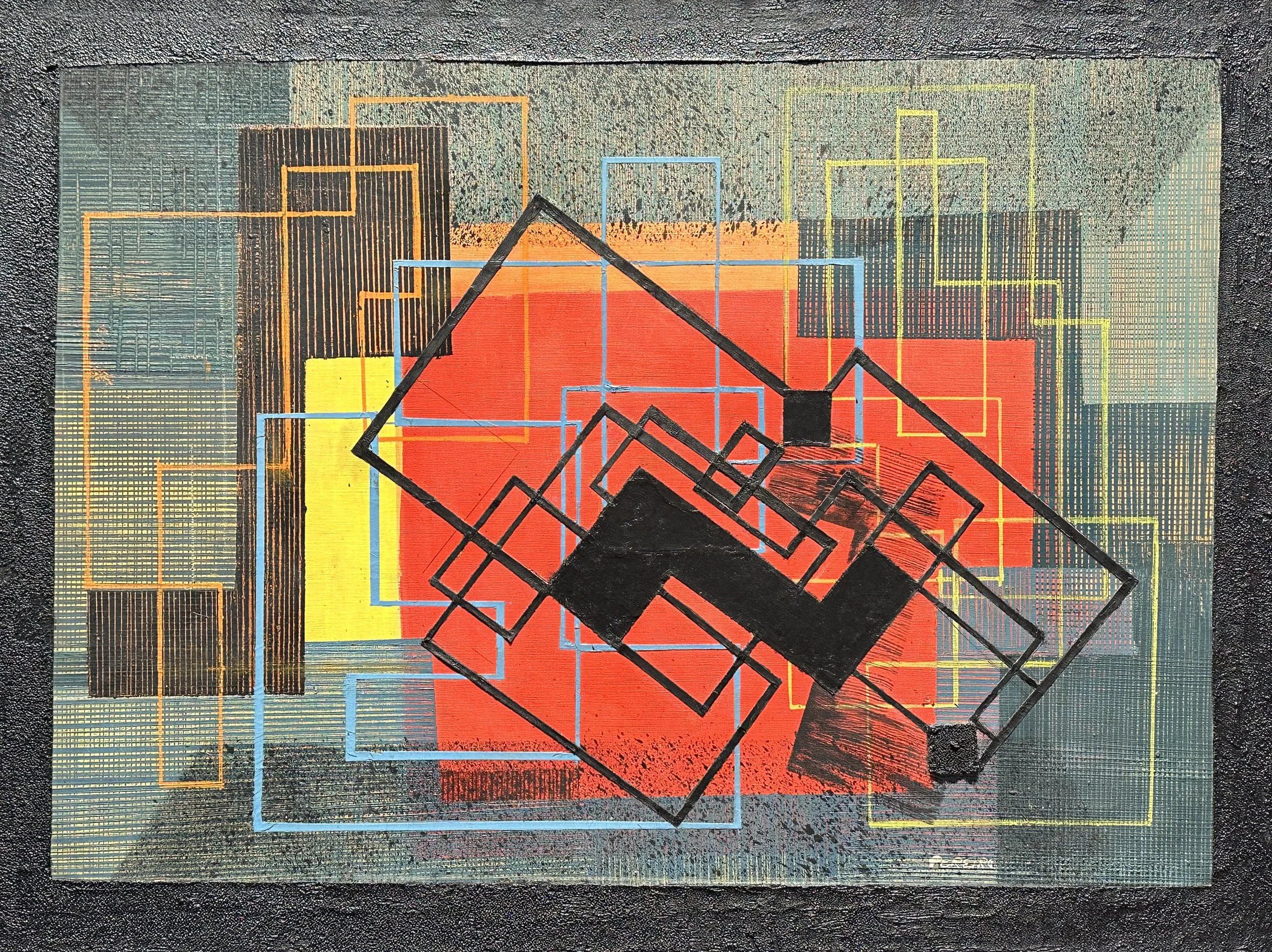

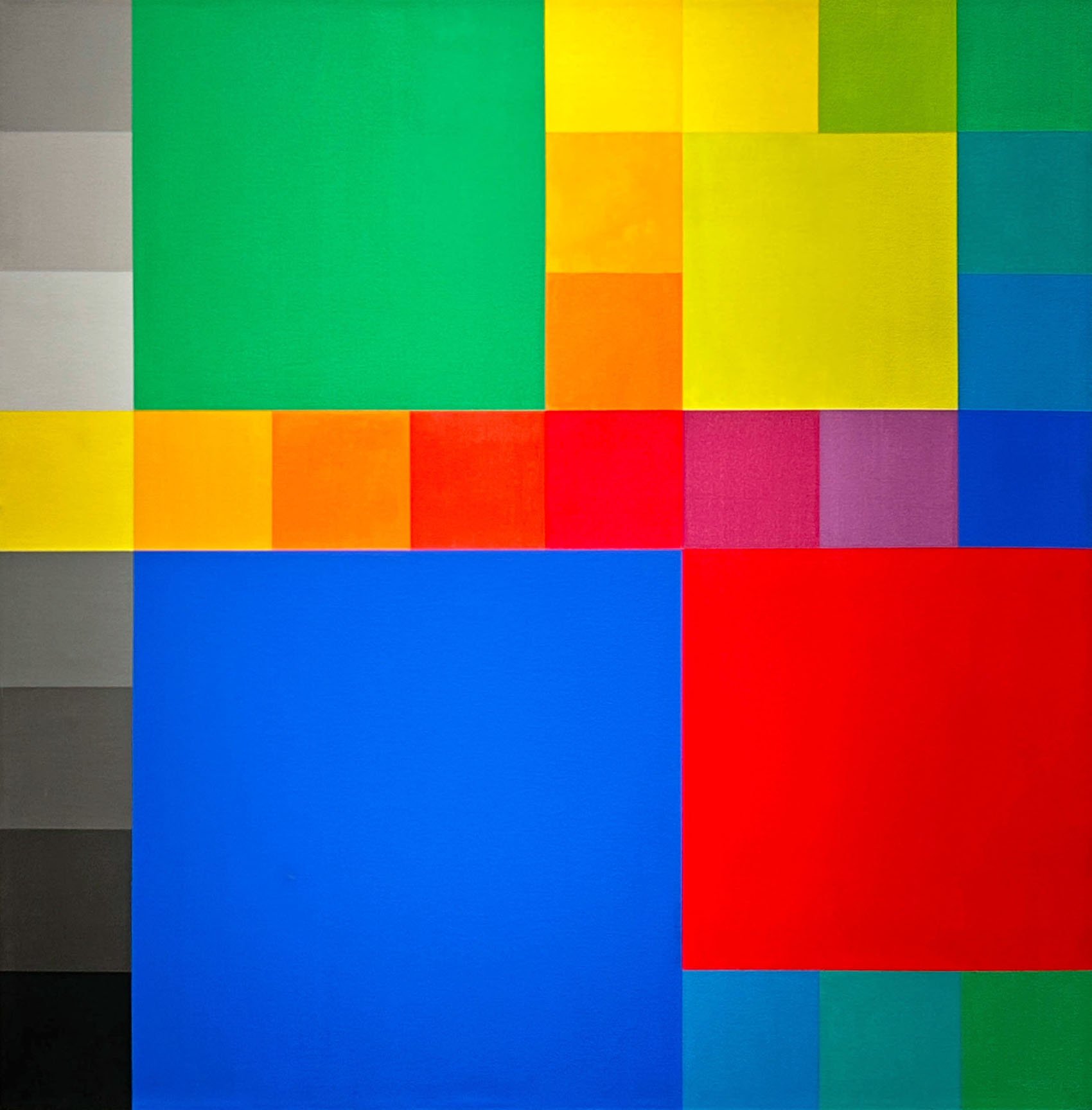

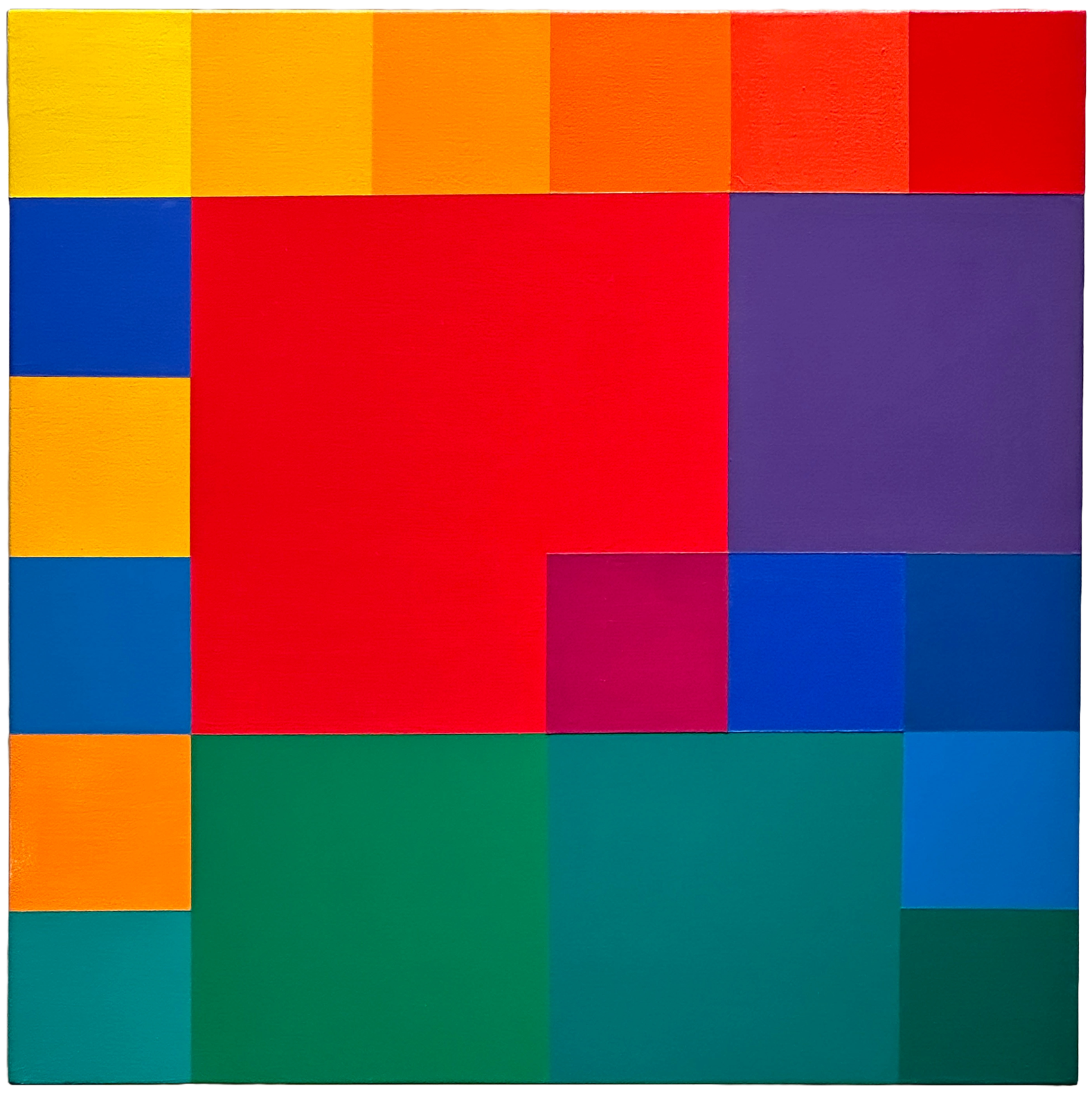

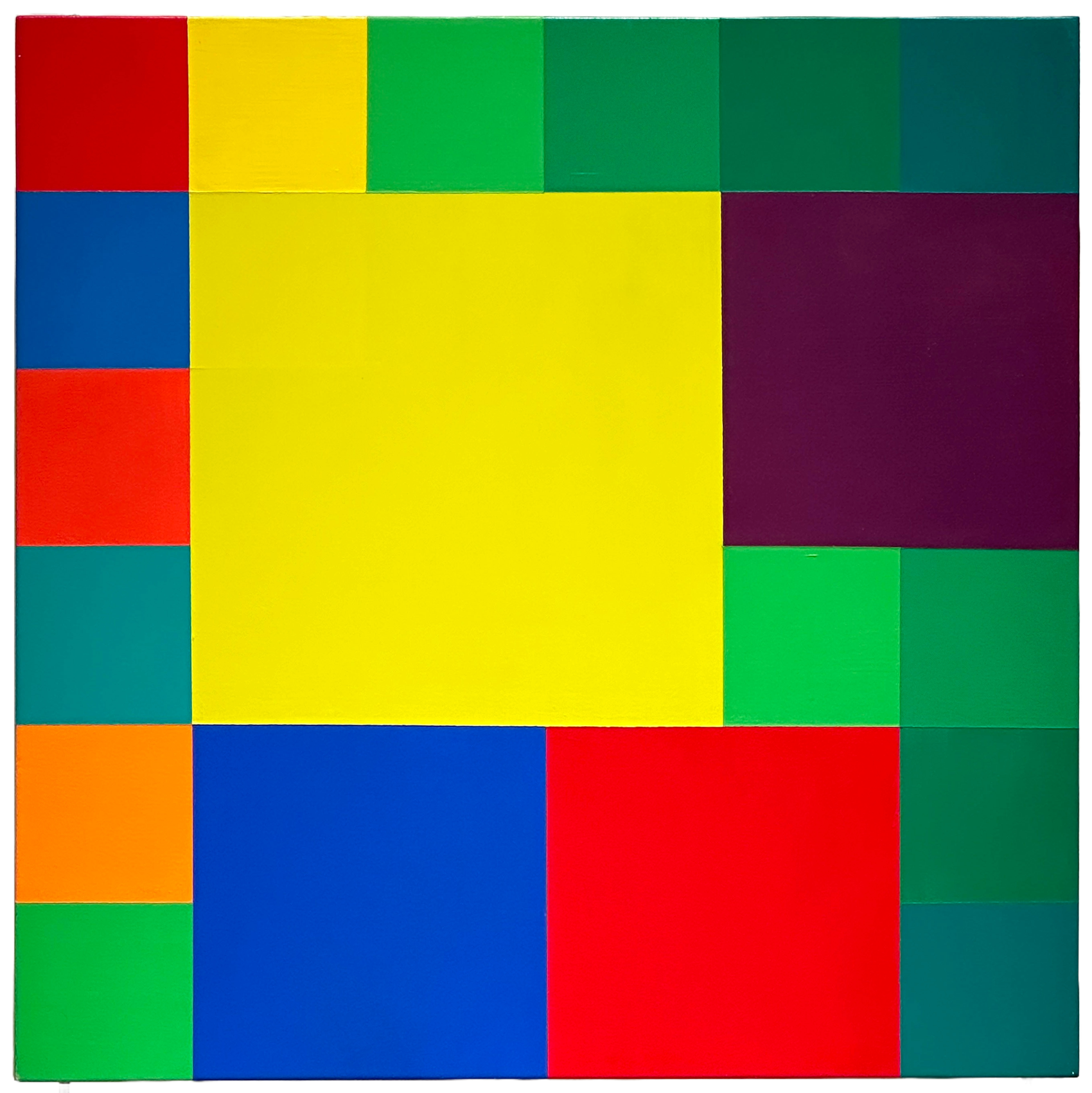

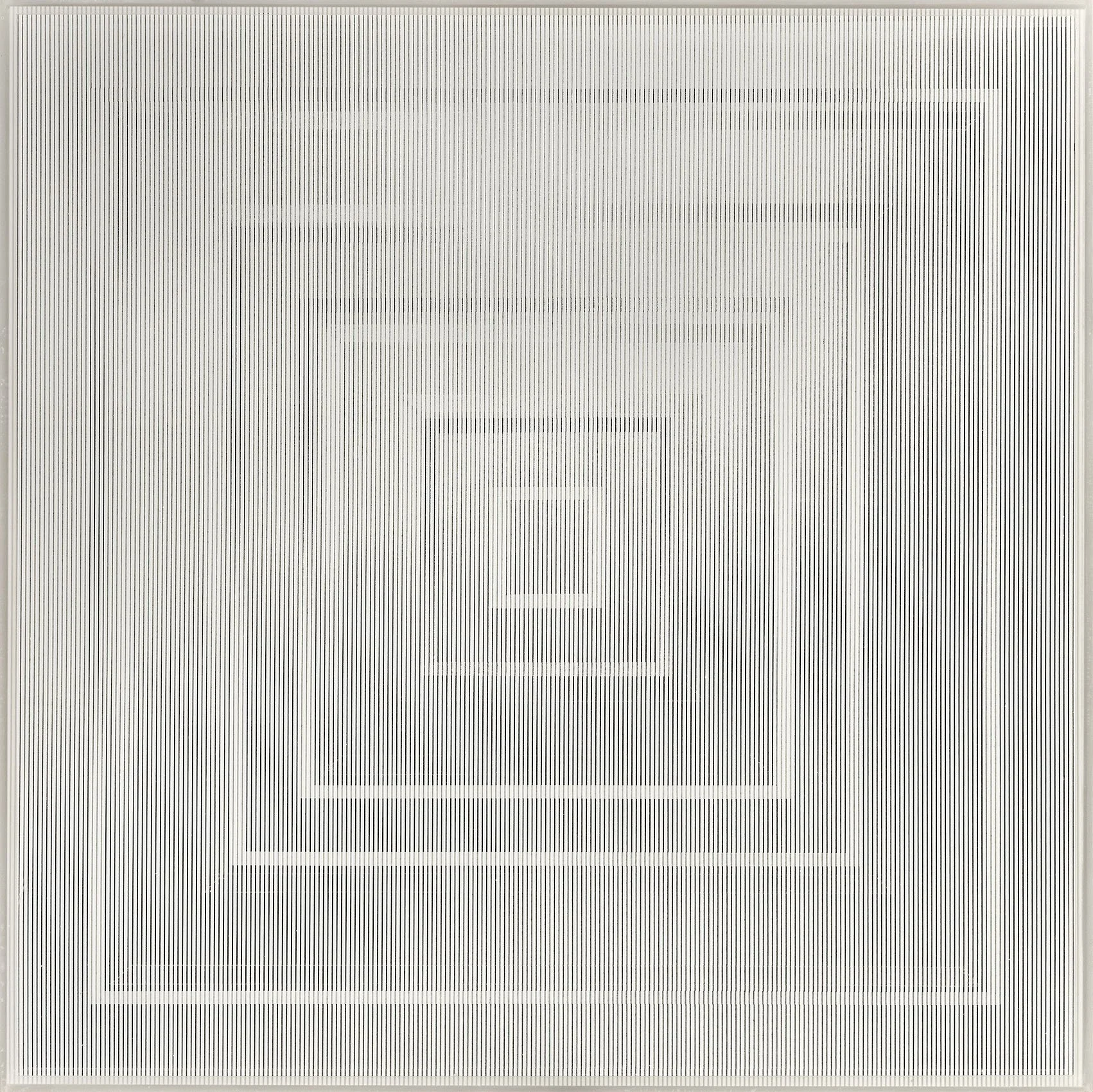

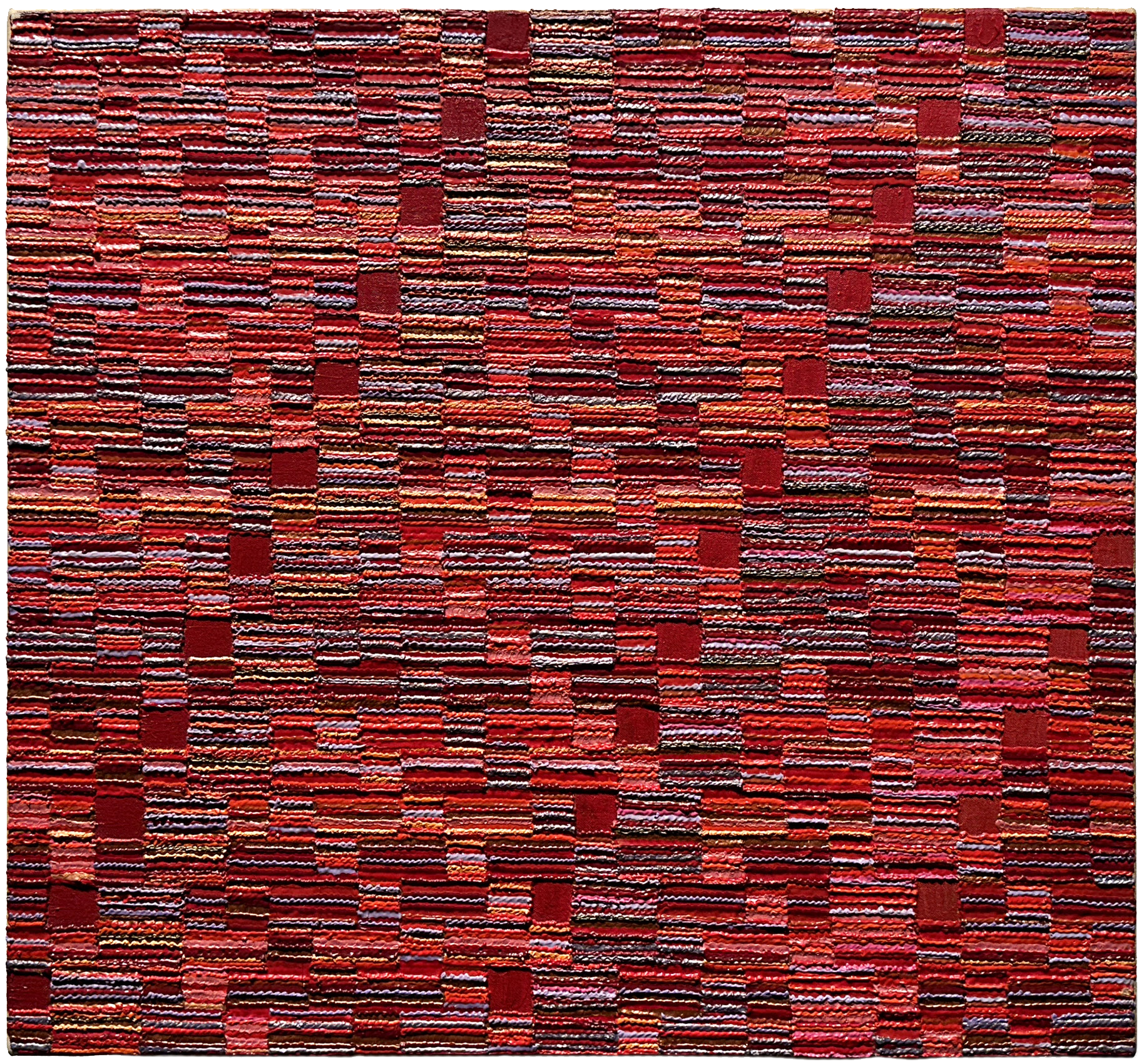

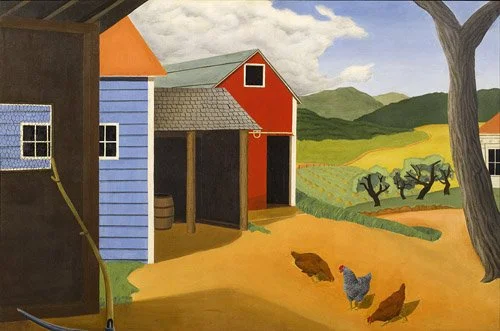

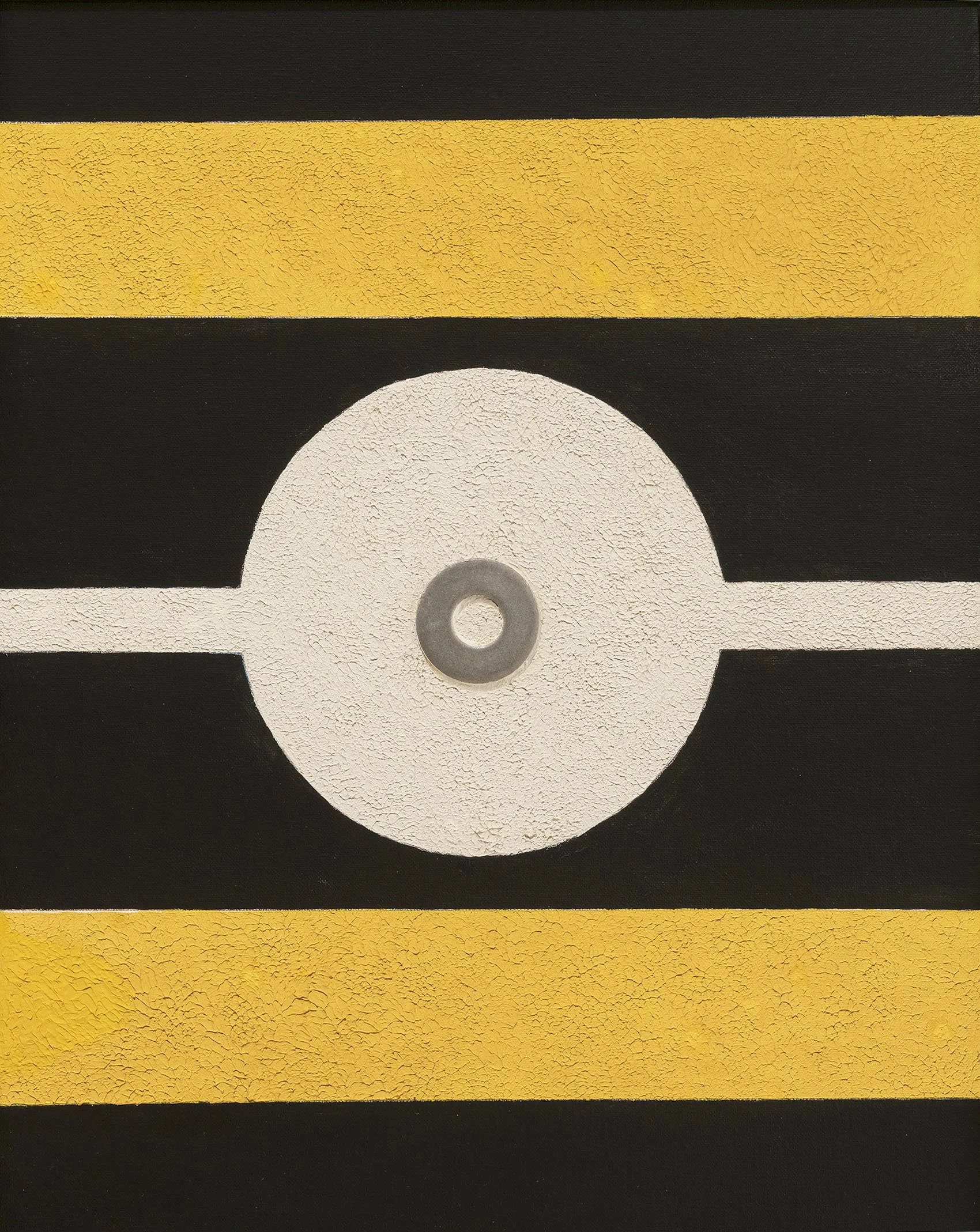

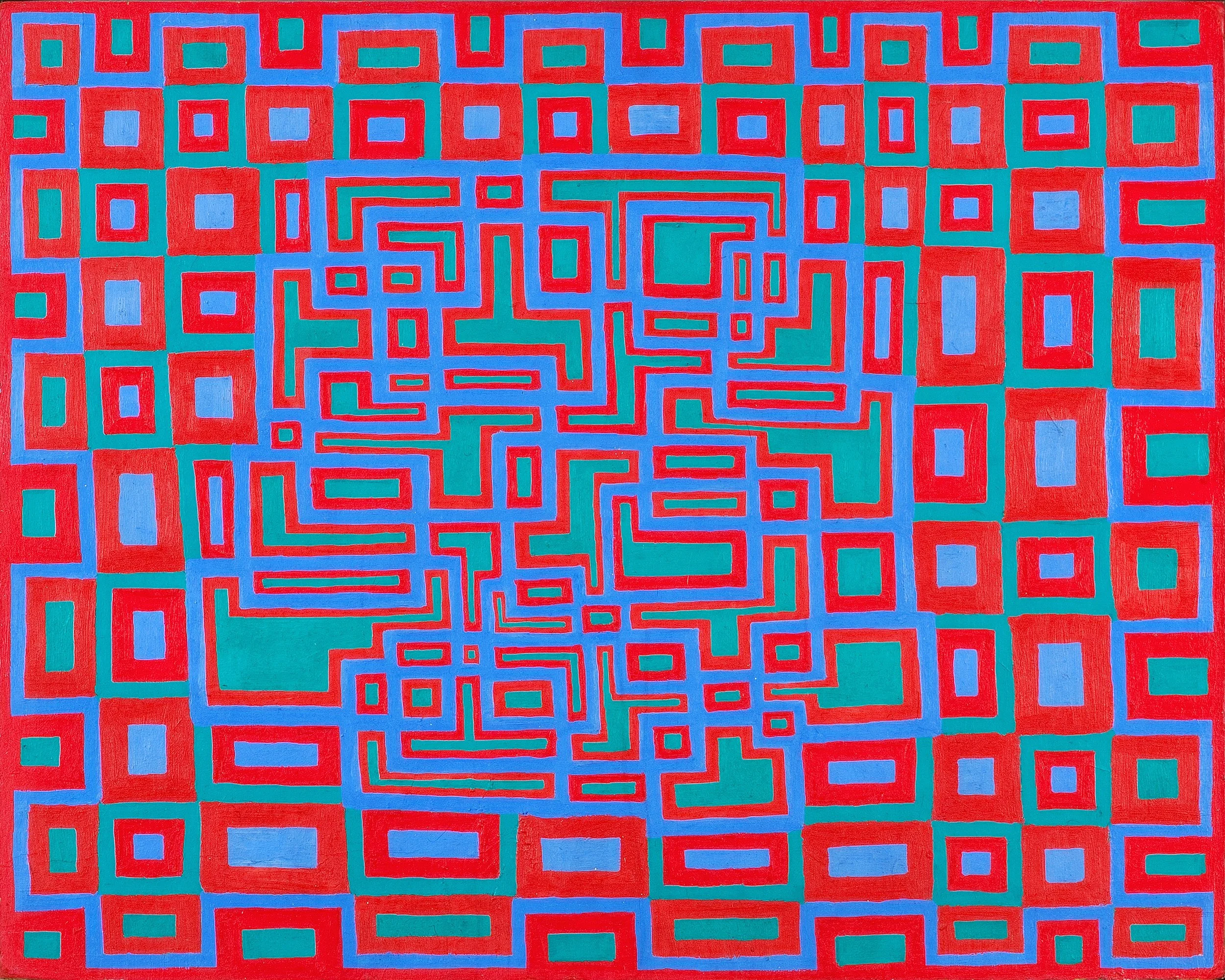

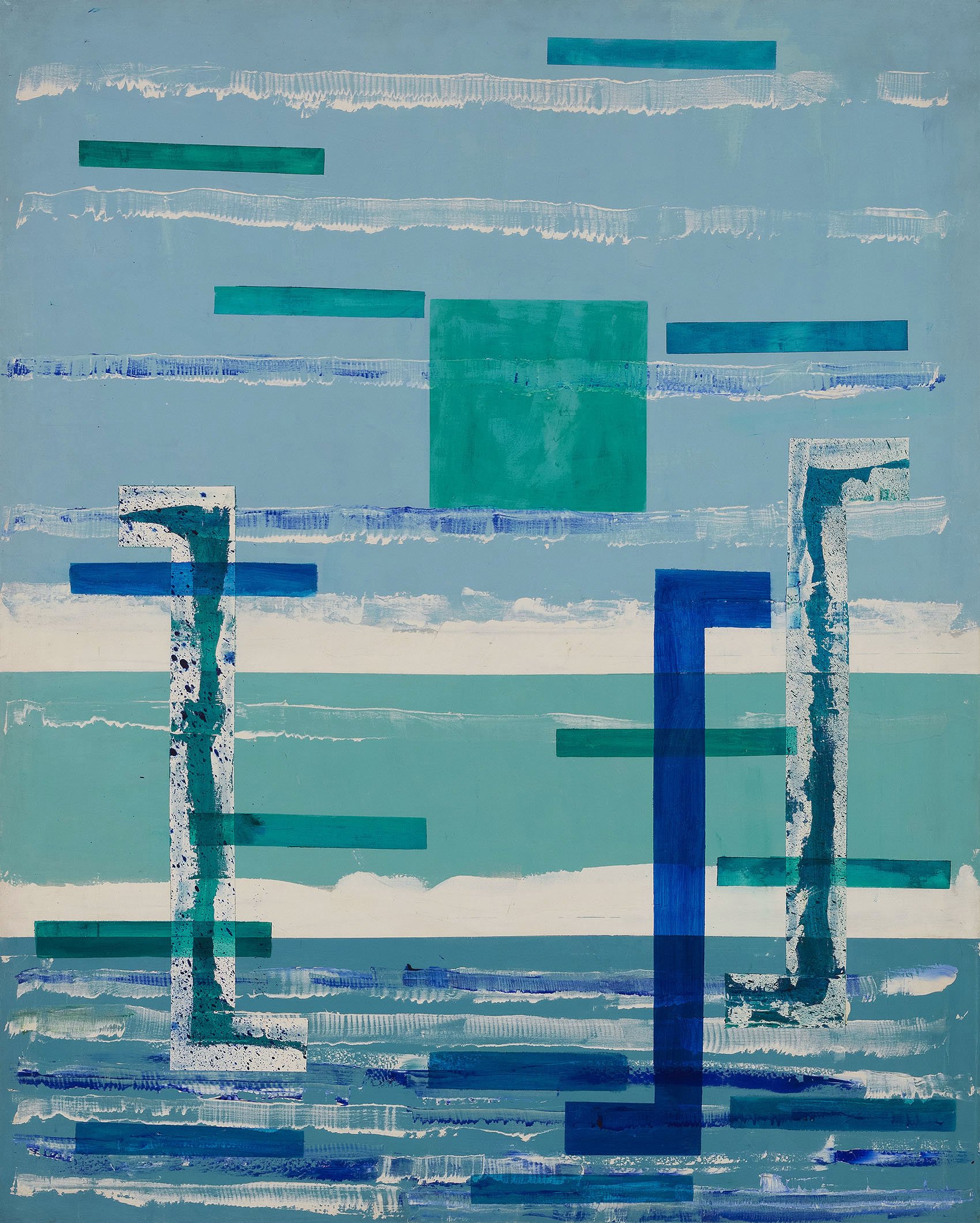

Paul Reed applied this new knowledge on transparency in the grid paintings of 1966. Lattices of colors draw attention to the transparency of acrylic paint and how overlapping paint layers create color differently when staining into raw canvas. In Intersection XII, 1966 in our exhibition the same three colors are used in the horizontal and vertical bands. The verticals are slightly lighter yet when two bands of the same color meet, a richer-toned square is created given the second layer sits “above” rather than “in” the raw canvas.

Interchange E, 1966

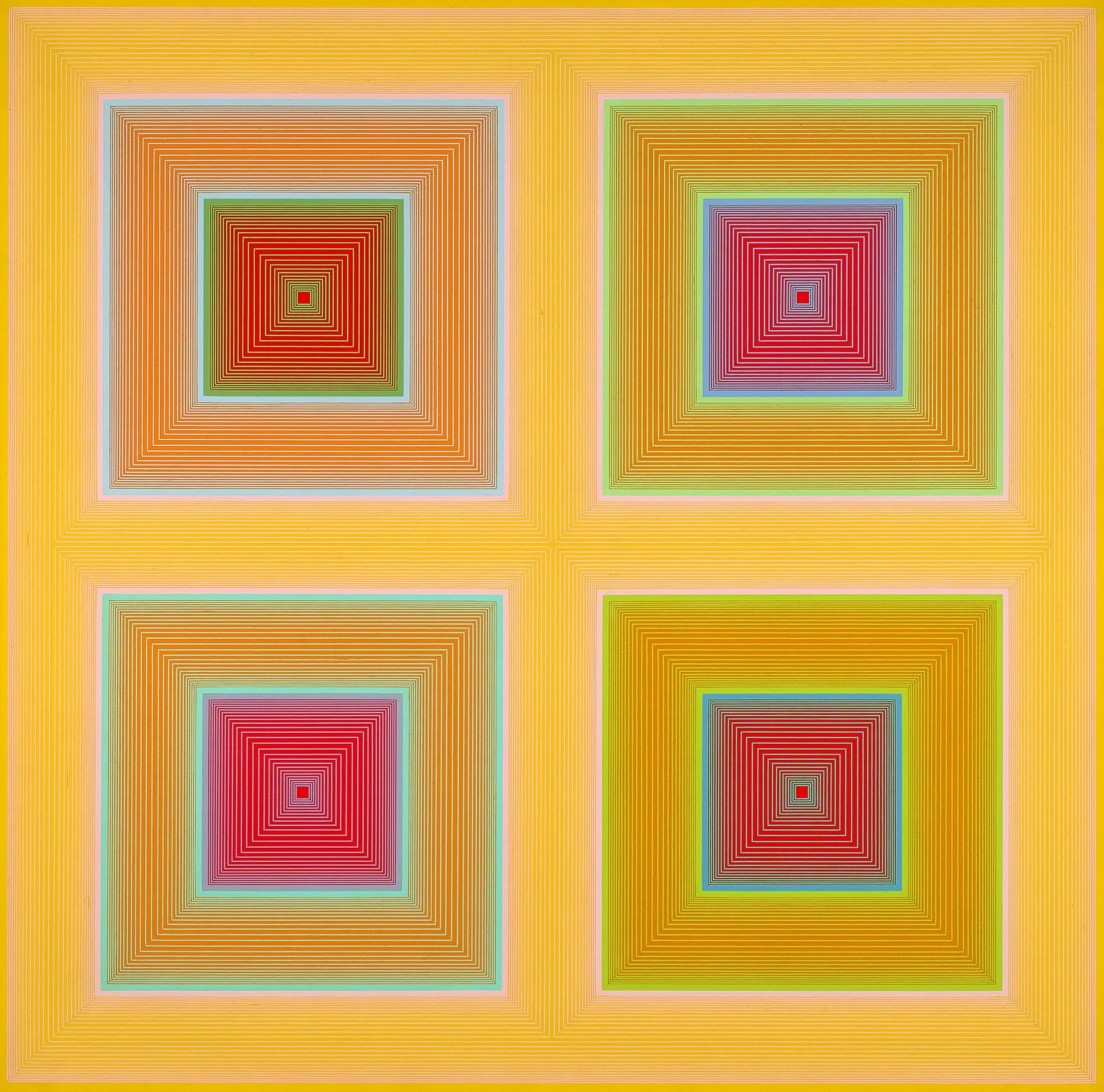

Paul Reed next looked for new ways to incorporate movement into geometric compositions. He found inspiration in Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles, 1952. Reed noted that the strong diagonal blue lines determined how the viewer’s eye moved across the canvas. This observation caused Reed to consider how cadences of color could guide the viewer in his own work. Reed found that zigzagging lines of color provided a simple, direct way for the eye to relate bands of color to the canvas support. The bands are made by overlapping two colors to create a third as seen in Interchange E, 1966 where purple and teal overlap to create a central navy blue. In these geometric works, Reed began to consider the overall form of the painting and how a shaped canvas could emphasize the power of color.

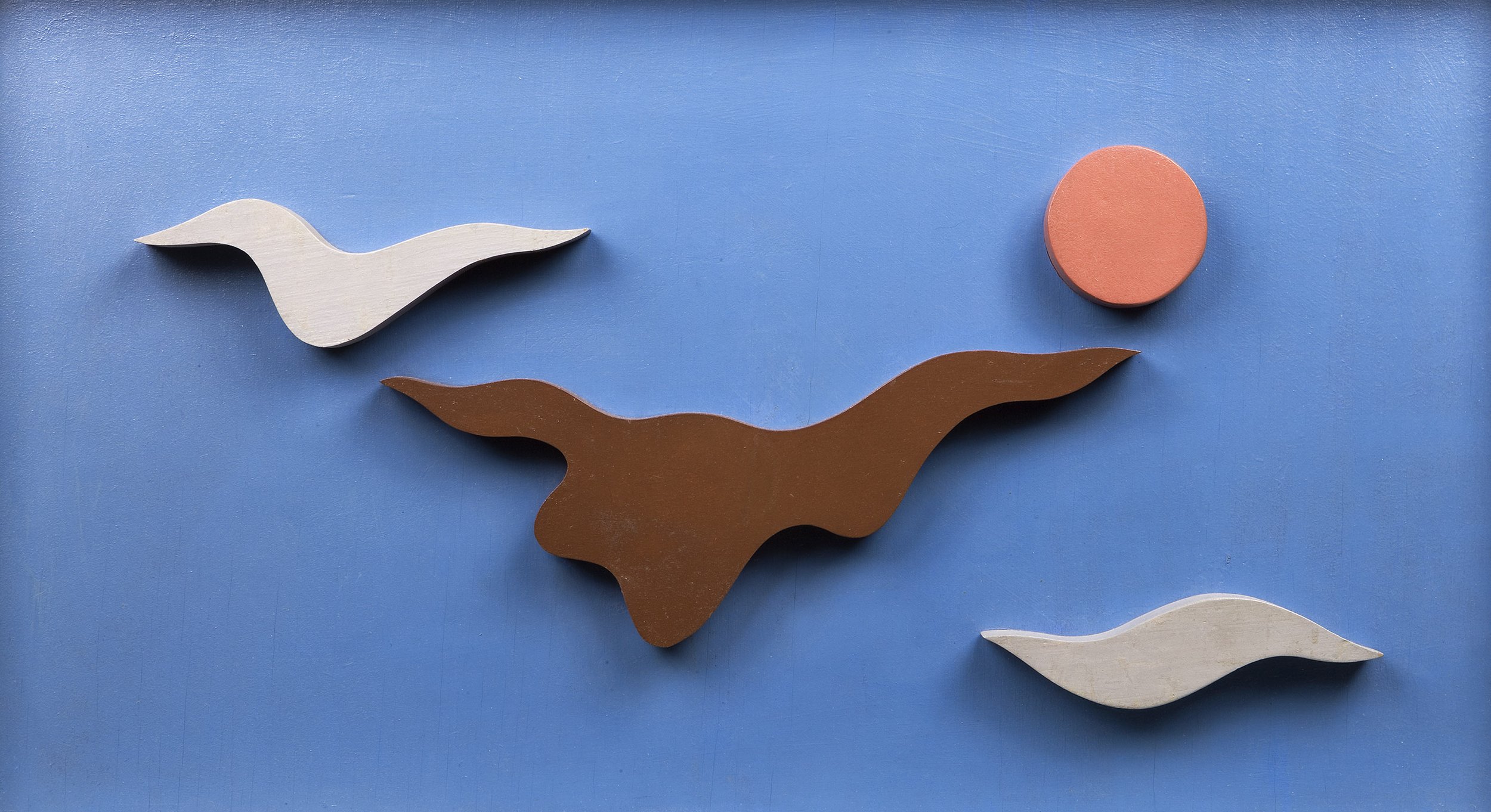

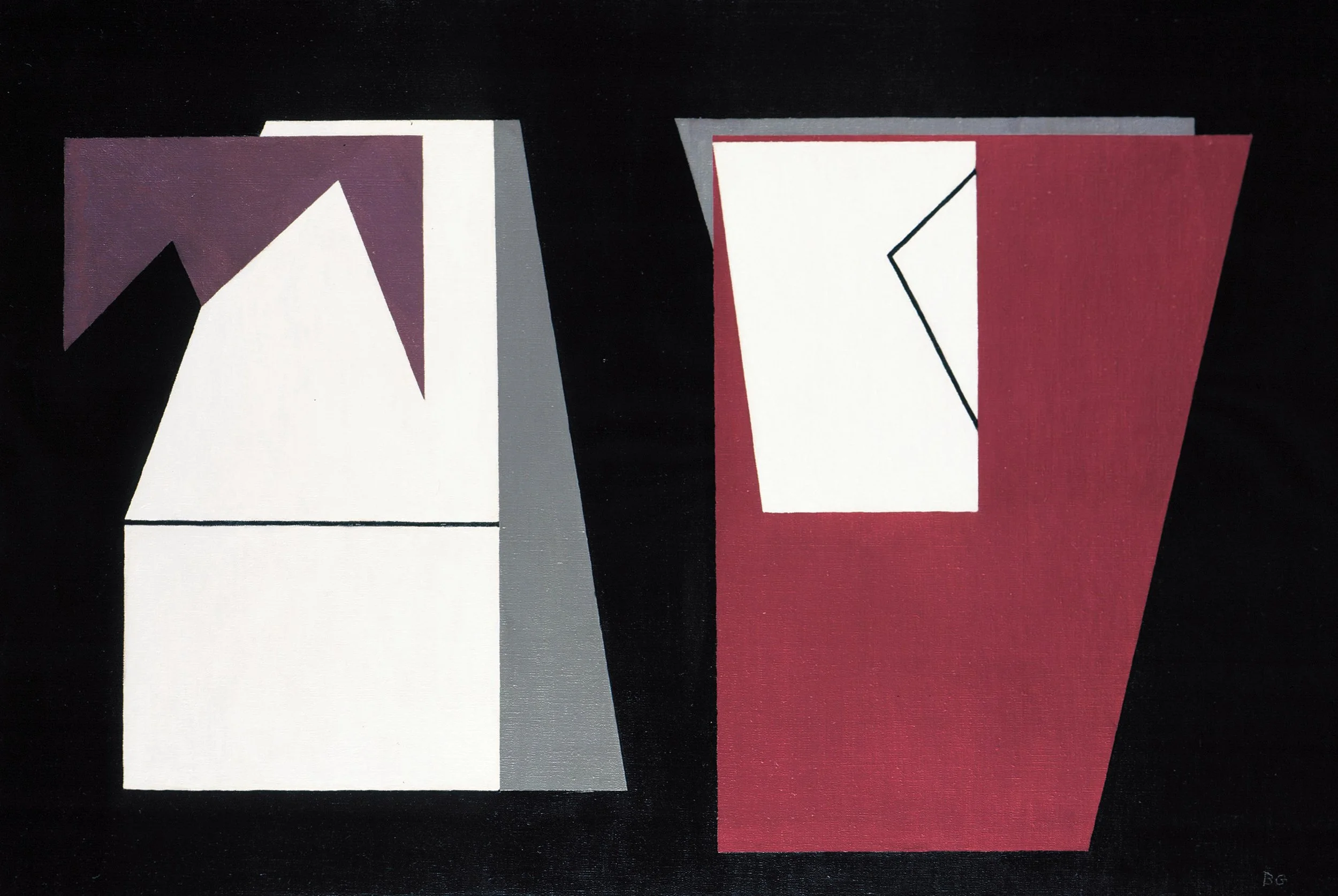

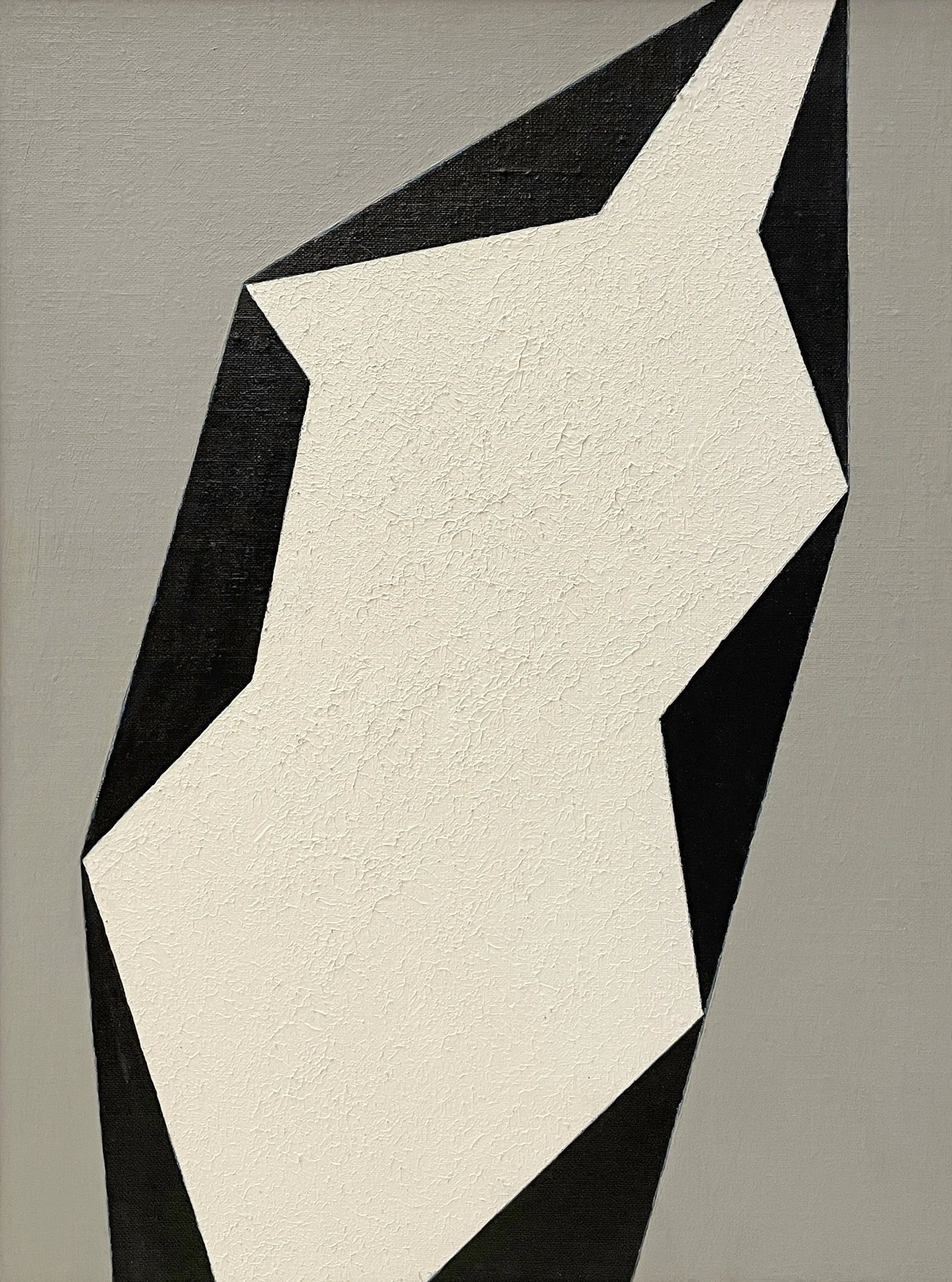

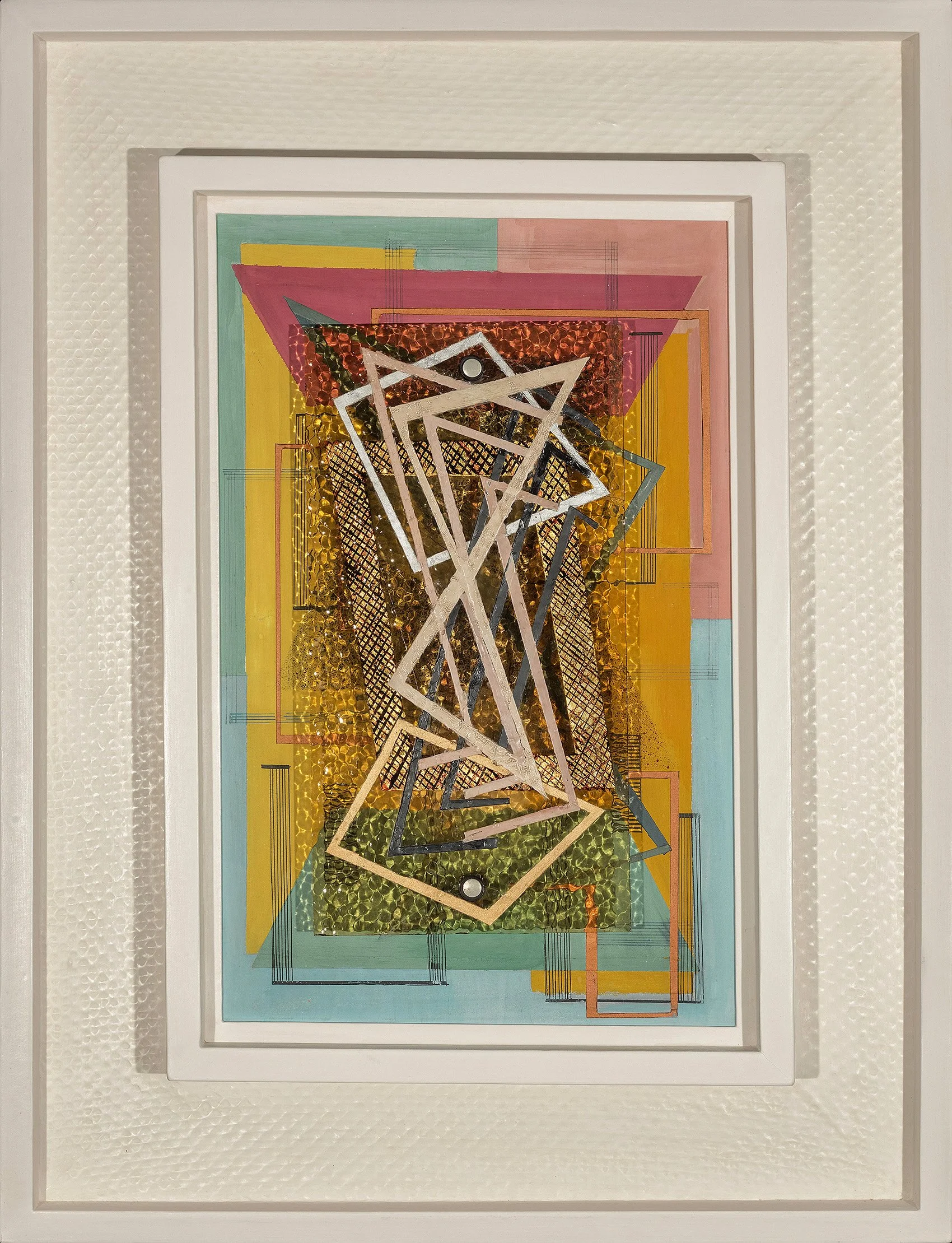

After working in diamond and lozenge shapes, Paul Reed was introduced to the work of California artist Ron Davis in the 1967 Washington Gallery of Modern Art exhibition A New Aesthetic curated by Barbara Rose. The exhibition of Minimalist sculpture with an emphasis on California artists included Ron Davis’ isometric projection shaped canvases in molded polyester resin and fiberglass. These works inspired Reed to twist and pull his grids to form a five-sided shape. The effect of color pushing out beyond the constraints of the canvas interested Reed so much, he experimented with increasingly complex shaped canvases through 1970. Our gallery exhibition has 2 shaped canvas works as well as related collages. We have loaned the large painting Safid to the Oklahoma City Museum exhibition.