7 WOMEN RETHINK FINE ART AND CRAFT

February 1 - April 26, 2024

Installation Views | Essay | Biographies | For availability and pricing, call 212-581-1657.

Installation Views

Photography by Renan Teuman

Essay by Emily Lenz

Abstraction in Fiber and Paint, 1976-1989

This exhibition looks at the blending of fine art and craft by women artists in the 1970s and 1980s working in abstraction. Anchored by the work of Miriam Schapiro, a leader of Feminist Art and the Pattern & Decoration group (P&D), the exhibition looks at painters who use or reference fabric and fiber artists who work in painterly ways. All the artists in our exhibition use abstraction as a universal language and a means to explore color. The connection between abstraction and textiles is ancient; the warp and weft of woven textiles are the earliest examples of grids dating back 24,000 years. In the 1970s, the incorporation of craft into fine art was a feminist statement to acknowledge centuries of anonymous women’s work. The artists in our exhibition looked back and forward in time, embracing references to craft and nature while using computers or algorithms to achieve their vision. They embraced the plurality of materials and content seen in contemporary art today.

In addition to Miriam Schapiro, we include the painters Gloria Klein and Dee Shapiro who set up systems to determine their compositions, resulting in patterned paintings that recall woven textiles. Both Klein and Shapiro were part of the Criss-Cross Artist Collective focused on algorithmic approaches to painting and were included in the first significant exhibition on Pattern Painting held at PS1 (now part of MoMA) in 1977, along with Miriam Schapiro. Both the Criss-Cross and the P & D artists were interested in the use of repeated patterns to move beyond the Minimalist grid and cover their painting surfaces with bold moving color. All three artists were also contributors to the Feminist art publication Heresies. The fiber artists selected for our exhibition Cynthia Schira, Sherri Smith, Kris Dey, and Diane Itter each used grids, geometric color progressions, and paint or dyes to create their works. They were included in significant museum exhibitions in the 1970s and 1980s as they pushed their art form beyond craft through ambitious scale, new techniques, and unexpected materials. They all were in The Art Fabric: Mainstream, a 1981 publication by Mildred Constantine and Jack Lenor Larsen that identified 125 international artists key to fiber art. The accompanying exhibition opened at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and traveled to nine other American museums. These artists proved false the notion that craft begins with material and technique while art starts with an idea, fusing the two to offer contemplation and awe to the viewer.

Art that crosses categories or definitions remains fresh today. Many of our gallery exhibitions identify moments when new materials or techniques advance art forward. The gallery has shown abstract painters taking on sculptural form in constructions in the 1930s and shaped canvases in the 1960s. Our study of new materials has led to exhibitions on how the development of acrylic paints led to hard edge, flow, and staining in the 1960s. In this exhibition, the treatment of dyed or painted fabric is a natural extension of 1960s stained and Op paintings. In a way, the 1960s formalist discussions on the stained canvas are realized by our fiber artists as their process, materials, and color are inseparable.

In past exhibitions, the gallery has highlighted the influence of Bauhaus artist Josef Albers’ color theory on generations of artists. In this exhibition, the importance of both Josef Albers and his wife Anni as teachers is evident. Anni Albers published a book on weaving in 1965, introducing a younger generation to her Black Mountain College teachings. When Anni went to study at the Bauhaus in 1922, she was pushed into weaving as even in that idealistic school, women were encouraged to enter fields of craft rather than painting, sculpture, or architecture. She went on to show how weaving exemplified the height of modernity, encouraging her students to study and experiment with the interaction between medium and process that leads to form. Anni Albers’ teaching from the 1930s to the 1960s was integral to the development of fiber art as its own art form.

The fiber artists included in this exhibition worked parallel to the Pattern and Decoration (P&D) group of post-modern painters who also looked globally and historically for decorative patterns to use in their art. Both the painters and fiber artists shared an interest in pre-industrial textiles of Africa, Asia, Indonesia, and of course the Americas with Peruvian textiles and American quilts. Textiles as an art form began in the 1960s when artists moved away from the wall, scaled up their work, and used natural fibers to make works without function. In the 1970s there was a noted return to order, structure, and beauty in fiber art. This new Classicism built on advancement in artistic intent while returning works back to the wall. The P & D group aimed to make beauty their subject as well. In the 2008 exhibition Pattern and Decoration: An Ideal Vision in America, held at the Hudson River Museum, critic John Perreault said P&D “reintroduced beauty, particularly historical, non-Western, and populist beauty, into art. With its valorization of the floral, the lush, the colorful, and the complicated, the movement was in part a response to the cool Puritanism of minimalism in painting and sculpture.”

In the early 1970s, Miriam Schapiro developed her personal style, femmage, incorporating found fabrics and materials considered decorative into her paintings. With all their flourishes, the paintings maintain an underlying grid, developed out of her 1960s abstractions mapped out with early computer imagery. In A Garden in Paradise, 1982, Schapiro outlined her heart-shaped canvas with a border of cubes in purple, pink, and black as a nod to her hard-edge past. Schapiro selected shapes like hearts and fans as references to feminine and decorative traditions, as well as the body. Schapiro’s 1980s shaped works use abstraction, decoration, fabric, and figuration to create subversive feminist statements and alluring beauty.

Gloria Klein was a member of Criss-Cross, a collective of pattern painters based in New York and Colorado. She developed a system of diagonal lines of varying lengths to distribute color across the painting’s surface marked out in a grid of 1-inch squares. This system of set lengths and positions freed Klein to focus on the application of color. She first set out pieces of ¼ inch tape across the canvas, painted the field a monochrome color, and then removed the tape to add hatch-marks of colors. She applied the brightest colors first across the surface according to the factorials of the painting’s width. She then intuitively invented patterns filling in the remaining hatch-marks to create clusters of color. In a 1981 Criss-Cross publication she described her paintings as “interwoven surfaces of complex density”. A 1980 review notes in Klein’s work that “geometric bits of color make up computeresque but ultimately sensuous surfaces.”

Dee Shapiro also described her work as interwoven. A fellow member of Criss-Cross, Shapiro first explored the Fibonacci series, used in the Golden Ratio, to determine the color arrangements of her compositions. Shapiro acknowledges the importance of domestic skills in her art, remembering how the counting and patterns of knitting captured her attention as a child. In the series Chromatism from 1978 to 1980, Shapiro’s patterns are intuitive, no longer mathematical, as she followed Josef Albers’ lessons in color interaction. She squeezed paint out of a tube directly onto the canvas, giving her surface a woven or beaded texture that is often confused at first sight with a weaving.

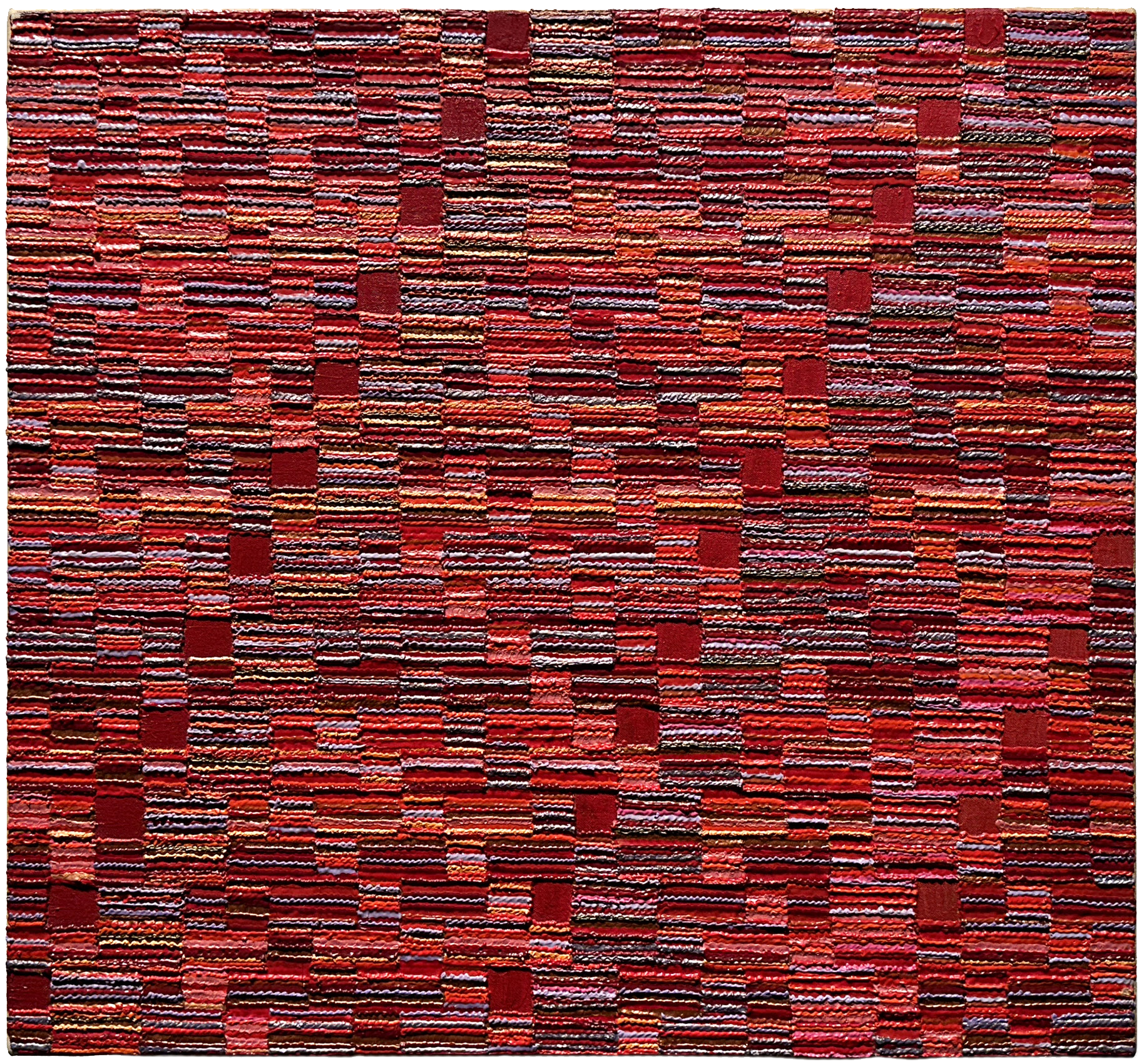

Sherri Smith was included in the Museum of Modern Art’s landmark 1969 exhibition Wall Hangings, credited with establishing fiber art as an art form. She braided hand-dyed industrial cotton webbing into box-like units that combine a geometric three-dimensional surface with planes of intersecting and shifting colors. Her choice to weave 1-inch wide fabric rather than thread translated into works of monumental scale. After graduating with an MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art, Smith designed jacquard-woven textiles for Dorothy Liebes and Knoll Fabrics in New York. She maintained her own studio and explored color in part out of an interest in nature, eschewing popular neutral coarse fibers. Her piece Volcano No. 10 was noted in the Wall Hangings catalogue for its gradation of color (orange, red, lavender, and purple) to reinforce its three-dimensional effect. In 1971 Smith left the textile industry and went on to start the first fiber arts program at the University of Michigan in 1974. In her process, Smith mapped out her geometric composition first, dyed the cotton webbing accordingly, and then began braiding. To obtain the desired result, Smith carefully worked out the patterning to maintain a single overall effect. Each side of the “cube” unit is differently colored creating prismatic patterns that shift as the viewer moves around the piece, as seen in Carnelian Tapestry, 1979 in our exhibition.

In contrast to the wide industrial bands Sherri Smith used, Diane Itter knotted fine linen threads usually associated with weaving or embroidery. She incorporated the geometry of Native American, Peruvian, and Ghanaian textiles into tightly composed arrangements of linen half-hitch knots. By the time Itter studied at Indiana University (graduating in 1974), hand-knot works by fellow students were made of coarse materials at a large-scale reflecting 1960s style developments. Instead Itter decided to work in a small scale using brightly colored threads. Her work was described as “miniature mosaics” in The Art Fabric: Mainstream. Every knot in Diane Itter’s work acts like a pixel; there are 400 knots per square inch (high-quality printed images are 300 dots per inch). Itter mapped out her geometric arrangements before starting a piece, which took over a week to complete. She pieced together small units of geometric arrangements to create a sense of overlapping and collage. Itter saw herself as both painter and sculptor, saying in a 1983 artist statement, “I paint with threads where color and structure are totally integrated and dependent upon one another.”

Cynthia Schira was an early adopter of the computerized loom which allowed her to weave in and out of three separate painted warps with discontinuous wefts of varying materials, colors, and sizes. Schira studied textiles at Rhode Island School of Design in the Fifties when the program trained students for the textile industry. This education exposed Schira to industrial processes like jacquard weaving, often said to be the first form of computing. In the 1980s Schira was one of the first weavers to use a computerized handloom. Her computer-assisted weaving (the computer handled the mechanical processes, not the design) freed her to use a painterly approach in finding her imagery as she worked. Schira had no issue with using computers in her practice, as she said “If you’re a weaver, you are using technology right from the very beginning. Every loom is a technological thing.” Schira’s work embraces innovative visual programs and complex weave structures, yet the impression for the viewer is poetry. Her multi-layered weavings expand beyond the grid to create an abstracted atmosphere that references nature without specific imagery.

Kris Dey was included in MoMA’s second major fiber exhibition Wall Hangings: The New Classicism in 1977. She used abstraction to convey the constantly shifting visuals of nature. In wrapping painted fabric, Dey expresses the changing patterns of nature without reference to identifiable forms. Both she and Cynthia Schira create an evocation of nature, rather than a replication. Dey studied at UCLA with Bernard Kester, a textile scholar who in 1971 organized Deliberate Entanglements at the UCLA Art Galleries, considered the first West Coast fiber art exhibition. That exhibition led Dey to make large, three-dimensional works at first, but with time she found herself focusing on color more than sculpture. Dey developed her technique of wrapping airbrushed fabric strips around contiguous tubes to create a luminous, atmospheric color field. She layered pattern and color by combining multiple designs with successive applications of paint. Using a repeating geometric pattern like Klein and Shapiro, Dey’s work emanates light because of the optic mixing of a limited range of colors. Her style is almost Pointillist. The unusual technique of hand wrapping and the vibrancy of her colors were a noted departure from fiber art in the 1960s.

Current exhibitions that confirm our interest in this period include Subversive, Skilled, Sublime: Fiber Art by Women (Smithsonian American Art Museum, May 31, 2024 – January 5, 2025, will include Miriam Schapiro and Cynthia Schira); Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, March 17 - July 28, 2024); and Weaving Abstraction in Ancient and Modern Art (Metropolitan Museum of Art, March 5 - June 16, 2024). With Pleasure: Pattern and Decoration in American Art 1972–1985 (MOCA, Los Angeles, 2019-2020 and Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College, 2021) included Diane Itter, Gloria Klein, Miriam Schapiro, and Dee Shapiro.