CYNTHIA SCHIRA

Available Work | Biography | Back to Exhibition

Biography • Cynthia Schira (b. 1934)

Cynthia Jones (later Schira) first studied weaving at the Rhode Island School of Design, where she earned her BFA in 1956. She intended to study art but accepted a scholarship only available to textile majors to pay her tuition. That was her serendipitous introduction to the loom and the art form that would engage her for the rest of her life.

The textile program at RISD was distinct from other art programs as most students were headed toward industry as textile engineers, chemists, or designers. In one of her courses, Schira learned to use an old Jacquard loom through a punch card system. This required diagraming weaves as the rise of each warp thread had to be designated on graph point paper. For one project, she worked 100 hours on the design diagram.

After graduation, Schira went to Aubusson, France to study with apprentice weavers at the factories where tapestries are woven in the traditional manner from preplanned cartoons. There she learned about artist Jean Lurcat and his call for artists to make cartoons specifically for tapestries. She would go on to participate in the International Biennales of Tapestry that Lurcat founded in 1973, 1977, and 1989.

On her return to the US, Cynthia married Richard Schira, a fellow student at RISD on the GI bill. In 1957 they moved for Richard to take a teaching position at the University of Kansas in Lawrence. In 1959-1960 the couple traveled to India when Richard had a Fulbright and then moved to Seattle for Richard’s MFA in painting. They settled in Lawrence in 1964 where Richard was a professor of painting and Cynthia pursued an MFA at the university. Her master thesis was on ancient Peruvian textiles as the 1962 English publication of Raoul d’Harcourt’s book on the topic was highly influential at the time. For her research, Schira traveled to Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology to photograph textiles collected by Junius Bird, curator of South American Archaeology at the Museum of Natural History. This firsthand exposure to fine examples of Peruvian weavings was important to Schira’s development. In 1967, she received her MFA from the University of Kansas where she then taught until 1999.

Schira’s first dealer was Marna Johnson in Chicago who started representing her in 1966. At Johnson’s apartment she saw the work of Lenore Tawney. Schira recalls Tawney’s Jupiter, 1959 had a critical place in her developing vision of her personal style; Tawney’s floating wefts stood out to Schira who perceived of her own supplementary wefts. Some of Schira’s early work included wide strips of aluminum as wefts in contrast to linen warps and the Supplementary Weft series in which she used bandages, tapes, ribbons, and other narrow fabrics added to the basic structural weft.

In 1971 Schira visited Deliberate Entanglements at the UCLA Art Galleries where she met Neda Al-Hilali and Lia Cook. This exhibition led Schira to differentiate herself from the first generation of fiber artists whose work was sculptural and architectural. She identified with the concerns of painting and looked for techniques to weave with the spontaneity of painters. While looking for more freedom, Schira remained committed to the two-dimensional, loom-woven plane. The grid-like geometry of weaving was both inspiring and liberating.

In 1981, Schira was invited to the Rhode Island School of Design along with 12 other fiber artists (including Lia Cook and Diane Itter) to experiment with Jacquard weaving in their artistic practices, working with the same loom Schira had used as an undergraduate. It triggered her interest in achieving more intricate weave structures aided by automation. She went to the Cooper-Hewitt Museum for further research on 19th century drawloom weavers. Schira was set on using computer technology in her practice as the computer and the loom are both based on binary principles. Weave structures are derived from two positions of the warp, up and down, just as computers perform tasks based on two positions, 0 and 1.

For Schira, weaving used both sides of the brain, writing:

One side utilizes the rational – with the math and graphing and planning that is needed to set the piece to the parameters of the chosen loom. The intuitive side plays with and into this set of structures: subjective, sometimes spontaneous visual decisions about color, form, and content. The coming together of the two kinds of thought/activity is what I found interesting.

A National Endowment for the Arts grant in 1983 allowed Schira to purchase a computerized thirty-two harness Macomber loom and to work for one year, which stretched into two, experimenting without commissions or shows. The computerized loom enabled her to select individual warp ends – some pieces require more than a thousand separate threads – on command facilitating an otherwise painstaking and unwieldy technical execution. The weaver no longer had the tedious job of changing tie-ups or connections between the treadles and the shafts. The computer remembered the structural weft sequences so that they could be changed and modified through the course of the weaving. This allowed the warp to be an active part of the composition rather than its passive structural role in traditional tapestry.

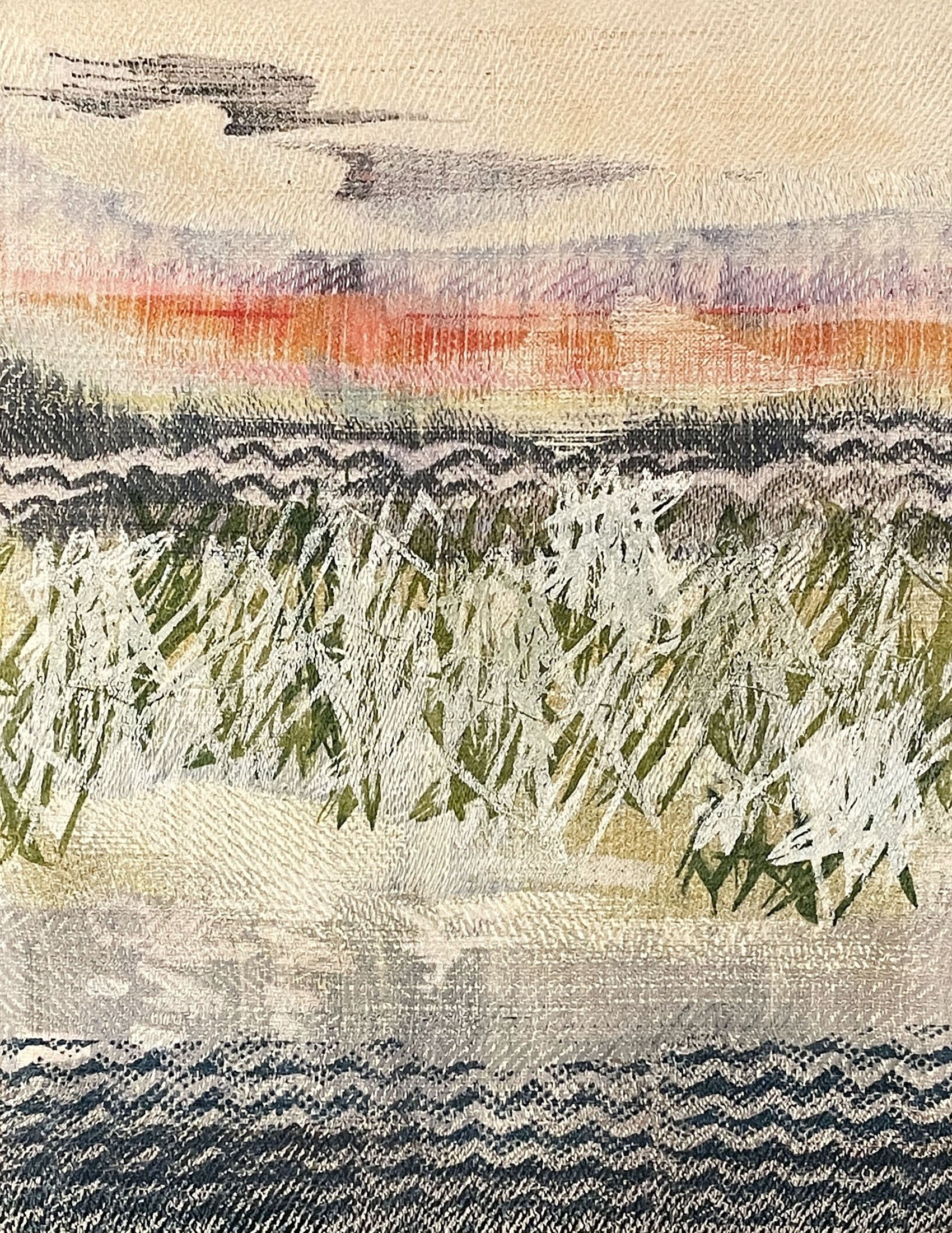

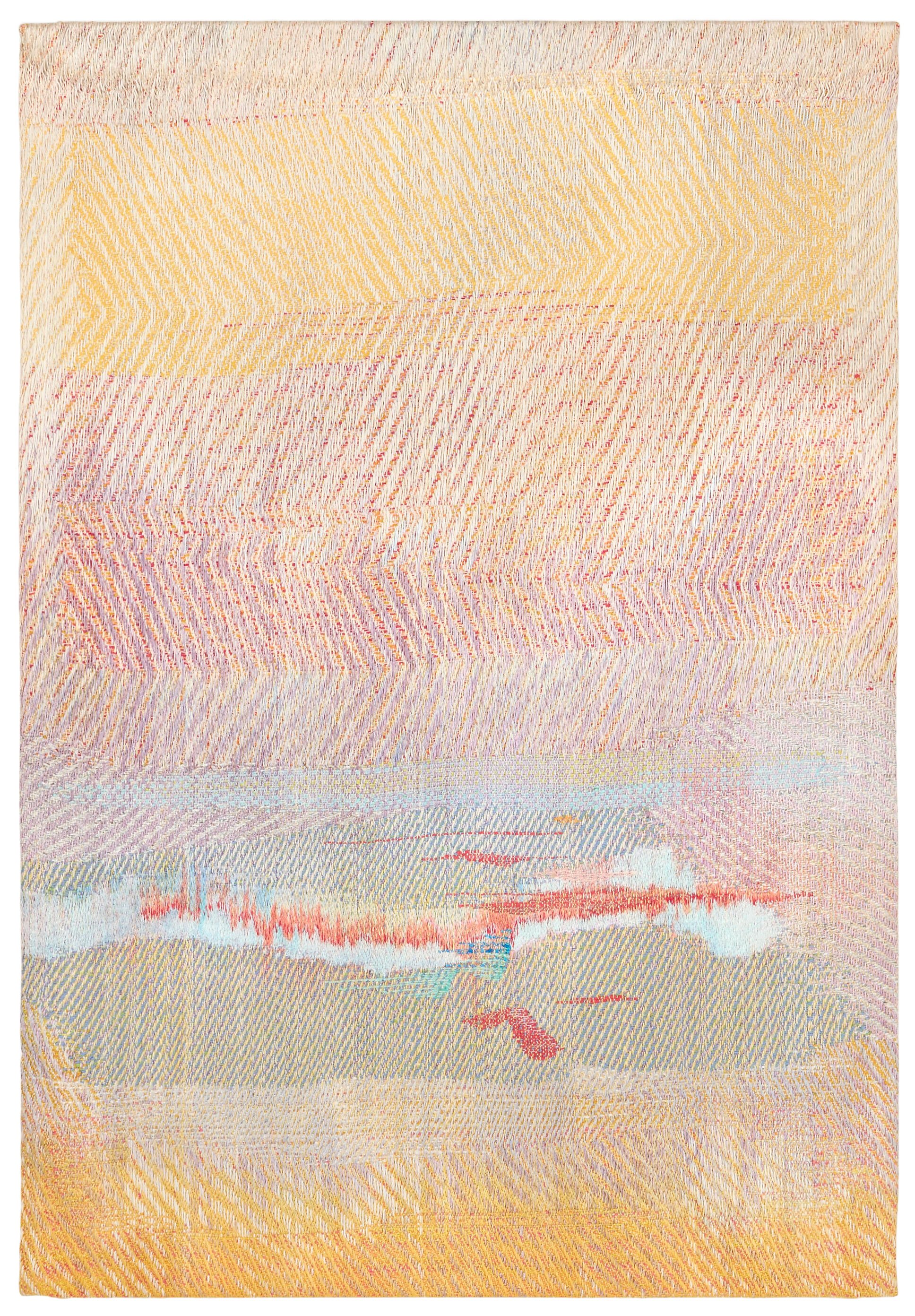

The first works resulting from Cynthia Schira’s experimentation were titled Woven Fields, which evolved into the works we are showing. The computerized loom allowed Schira to incorporate three warps into her weaving. On each she dyed or painted a different image onto the sets of threads. Rather than cover the warp threads completely, Schira used a discontinuous weft to reveal or conceal the imagery painted on the warp sets. The image and the physical structure of the cloth are indivisible. Schira describes the works as integrated triple-cloth with painted warps.

Schira incorporated different weave structures within a work so the viewer sees juxtaposing shapes defined by colors, thick or thin threads, and textural changes. These areas of color arise, fuse, and diffuse with a painterly fluidity that evokes a sense of place, frequently the open horizons of Kansas or summers on Lake Champlain, New York. Schira said of her work: “Although the reference is to a particular time or place, I wish to have the whole suggestive rather than definitive, and the viewer’s response emotional rather than analytical.” Schira skillfully balances new technology and the poetry of nature.

Cynthia Schira received much museum and academic attention in the 1980s. In the catalogue for her 1987 exhibition at the Spencer Museum of Art and the Renwick Gallery at the Smithsonian, the curator Nancy Corwin described Schira’s work as painterly. In her weavings, Schira captures light and space and their relationship with solid form. She achieves effects like smudging associated with pastels on paper or washes of watercolor. Each weaving begins with sketches on paper and then Schira paints the warps to indicate ideas, directions, and possibilities. Schira then works intuitively, adjusting the composition as she goes. The result is not a translation of a painting onto cloth like a traditional tapestry, instead she fuses painting and weaving together. A 1985 New York Times review noted Schira’s ability to “convey the brush strokes of Japanese landscape paintings.” The textile scholar Charles Talley said: “The frontiers between art, craft, and high technology appear to meet, merge, and dissolve in the collection of evocative landscape weavings produced by fiber artist Cynthia Schira.” [Artweek, April 16, 1988]

Schira’s work has continued to evolve using digital design software. In 1989 she was given an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts from RISD and in 2000 she received the American Craft Council Gold Medal in recognition of her lifetime achievement.

Schira’s work can be found in many museums including: Art Institute of Chicago, IL; Cooper Hewitt Museum, New York, NY; DeYoung Museum, San Francisco, CA; Indianapolis Museum of Art, IN; Joslyn Museum, Omaha, NE; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA; Museum of Art and Design, New York, NY; Philadelphia Museum of Art, PA; Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC; Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence; and Wichita Art Museum, KS.

Major Exhibitions

Forms in Fibers, Art Institute of Chicago, IL, 1970

Objects: USA, The Johnson Collection of Contemporary Craft, Smithsonian National Collection of Fine Arts (now Smithsonian American Art Museum), Washington, DC, traveled to 23 American and 11 European museums [Schira]

The Dyer’s Art: Ikat, Batik and Plangi, Museum of Contemporary Crafts, New York, 1976, traveling exhibition (curator Jack Lenor Larsen)

The Art Fabric: Mainstream, San Francisco Museum of Art, CA, 1981, traveled to 9 further museums

Craft Today: Poetry of the Physical, American Craft Museum (now Museum of Arts and Design), New York, NY, 1986

Fiber R/Evolution, Milwaukee Art Museum, WI, 1986

Cynthia Schira: New Work, Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence and Renwick Gallery, Smithsonian Institute, Washington, DC, 1987

Generations/Transformations: American Fiber Art, American Textile History Museum, Lowell, MA, 2003

An Errant Line: Ann Hamilton & Cynthia Schira, Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence, KS 2013

Game Changers: Fiber Art Masters and Innovators, Fuller Craft Museum, Brockton, MA, 2014

Threaded Visions: Contemporary Weavings from the Collection, Art Institute of Chicago, IL, February 24 - August 26, 2024

Subversive, Skilled, Sublime: Fiber Art by Women, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, May 31, 2024 – January 5, 2025