September 7 - November 11, 2022

Installation Views | Essay | For availability and pricing, call 212-581-1657.

Installation Views

Essay by Deedee Wigmore

D. Wigmore Fine Art presents Paul Jenkins (1923-2012): Lyrical Abstraction with 15 acrylics on canvas and 3 watercolors executed between 1960 and 1979. This exhibition focuses on Paul Jenkins’ mature work which arrived with the introduction of water-based acrylic paint around 1960. To give viewers an idea of why Paul Jenkins deserves their attention, here is a list of some of Jenkins’ most important museum exhibitions during the 1960s and 1970s. Below you’ll find the story of how Paul Jenkins developed his unique style as an Abstract Expressionist.

1960 - Important Launch

60 American Painters, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis

1961

Abstract Expressionists and Imagists, Solomon R. Guggenheim, New York

1962

Art Since 1950, World’s Fair, Seattle

1962 -1964

Art USA Now travels to museums in America, Europe and Japan

1963

New Acquisitions, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

1964

Painting and Sculpture of a Decade, 1954-1964, Tate Museum, London

1965

Painting without a Brush, Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, also includes: Chamberlain, Frankenthaler, Louis, Noland, Olitski, Pollock, Riopelle

1967

The 1960s: Paintings and Sculpture from the Museum of Modern Art Collection, MoMA, New York

1968

Dada, Surrealism, and their Heritage, Museum of Modern Art, Art Institute of Chicago, and Los Angeles County Museum of Art

1971

First American museum retrospective, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, travels to the San Francisco Museum of Art

1972

Paul Jenkins, Discoveries in Watercolor, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, travels to museums across the United States through 1974

Abstract Expressionism: The First and Second Generations in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, also includes: Gorky, Gottlieb, Graves, Hartigan, Hofmann, Kline, de Kooning, Marca-Relli, Mitchell, Motherwell, Rothko

1974

Inaugural Exhibition, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC

The 1960’s: Color Painting in the U.S., University Art Museum (now the Blanton), University of Texas, Austin

1977

Selections from the Lawrence H. Bloedel Bequest, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Born and raised in Kansas City, Missouri, Paul Jenkins’ interest in art began with frequent visits to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art where he was drawn to its Asian art collection. While a high school student, Jenkins experienced the chemistry of painting working summers in a ceramics factory. Watching expert artisans at work, Jenkins witnessed the tension in timing the correct moment to add something in an artistic creation. After serving in World War II, Jenkins used his military service benefit to attend the Art Students League in New York from 1948 to 1952. Jenkins’ four year course at the League occurred during the advent of Abstract Expressionism, a style which saw painting not as a recording of an object or place but as an emotional event. Meeting Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman, Jenkins realized his own artistic goal was to transform intangible feeling into valid pictorial forms. He saw that Pollock did this in woven webs of paint while Rothko achieved it using tonal fields of color as containers of light. Jenkins noted that both Pollock and Rothko achieved structure while leaving no trace of brushstrokes. In becoming an Abstract Expressionist, Jenkins discarded deeper perspective, recognizable subject matter, a contained composition, and standard brush use. Perhaps remembering the glazes melting, flowing, and interacting in the kiln at the ceramics factory helped Jenkins discover his unique painting technique.

Paul Jenkins worked flat, pouring layers of liquid enamel paint onto primed and gessoed canvas. He thinned his pigments so the paint could flow and spread, manipulating the paint and canvas using brushes and gravity within the time it took to dry. In 1956 he discovered that chrysochrome enamel out of a tube could be used to create a precise line. New materials along with techniques were acquired by experimenting with dripping, staining, and achieving contrasts between thickened and thinned pigments. Painting wet on wet, the colors interacted to suggest an imaginary space. As Jenkins developed the ability to guide the colors in a controlled improvisation, he could make forms appear in that imaginary space. Over the 1950s, Jenkins mastered both the creation of projecting masses and the manipulation of puddling, melting, and blending of colors to suggest movement not only across the surface but also beneath it. He courted chance occurrences or accidents and incorporated them into his compositions. Jenkins recognized that change and transformation underlies all existence and strove to communicate this in his art.

Around 1959-1960 Paul Jenkins made a gradual change from oil paint into newly developed water-based acrylics. With this development, artists no longer had to thin their paints with turpentine, which dampened the color; paint could now be both vibrant and transparent. This allowed Jenkins to explore luminous transparency and gain even more fluidity. His use of thinned flows and veils of color to consolidate his composition made Paul Jenkins different. He worked with paint factories in New York, London, and Germany to find paints that offered consistency and longevity. Also in 1959, Jenkins began to work consistently in watercolor on white rag paper. This led him to discover the paper added another kind of light to a painting, which added impact to the image set against the white ground. This experience with watercolors led Jenkins to use the white ground of his primed canvas in the same way.

Paul Jenkins began to preface the titles of his white ground paintings with the word Phenomena followed by a poetic expression of the attitude he felt his painting stated. The Phenomena paintings executed in acrylic were controlled with the use of a new tool, an ivory Eskimo knife. The ivory knife could be pressed against the sensitive tooth of the canvas without abrasion while allowing shaping and control of the acrylic paint flow. If brushwork was needed to perfect a shape, it was applied carefully to eliminate any trace of strokes. By 1960 Jenkins had a range and repertoire of skills that allowed his gestures while painting to be intuitive, free, and liberating. Chance still played an important role as the shape or image in a composition was discovered while working the ebb and flow of translucent pools of thinned poured pigment. The placement of compositional forms within the canvas edges was another result of courting chance in Jenkins’ creative process. Jenkins’ imagery was a fusion of observation and response emerging as if it just happened- like a phenomenon.

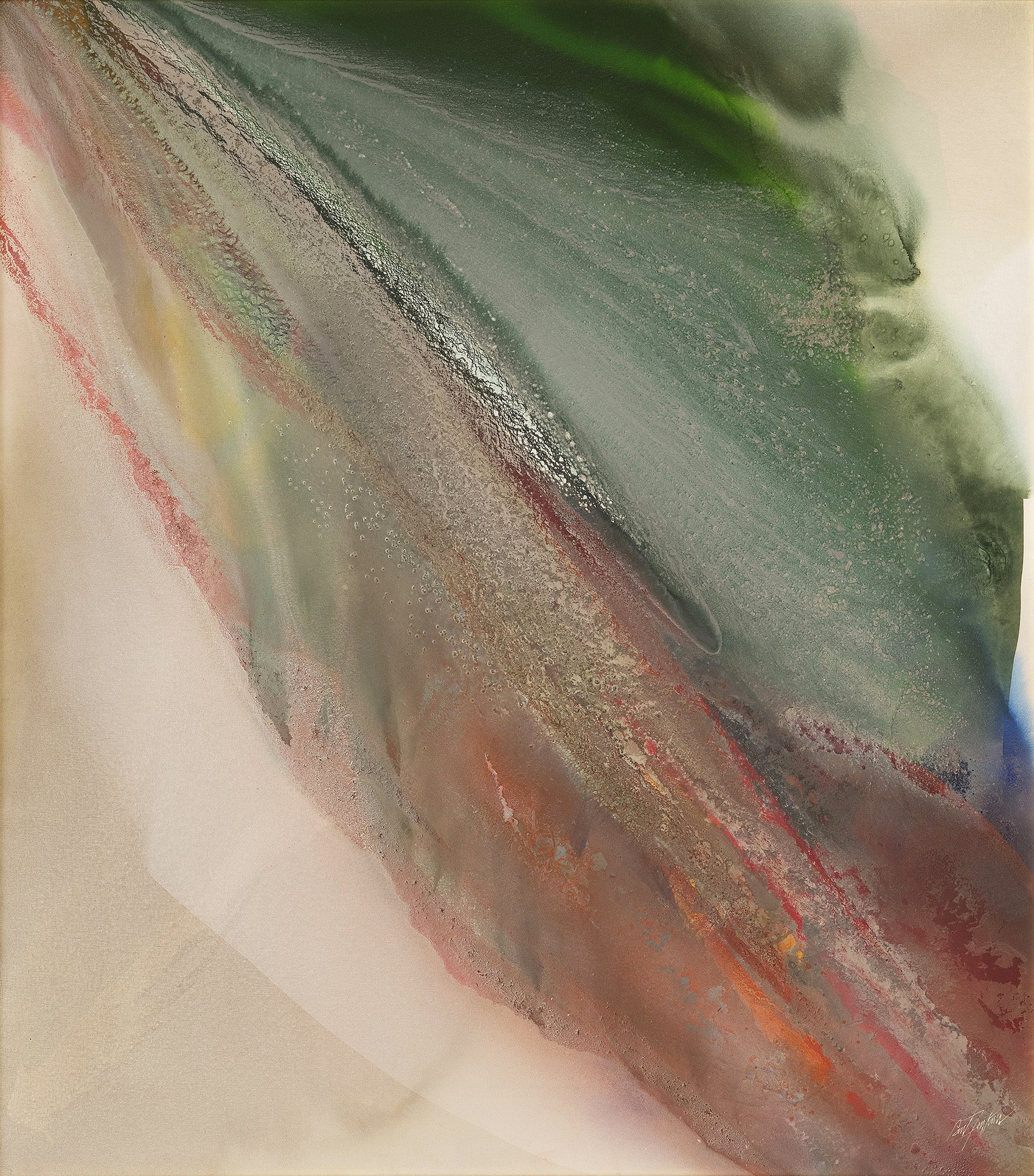

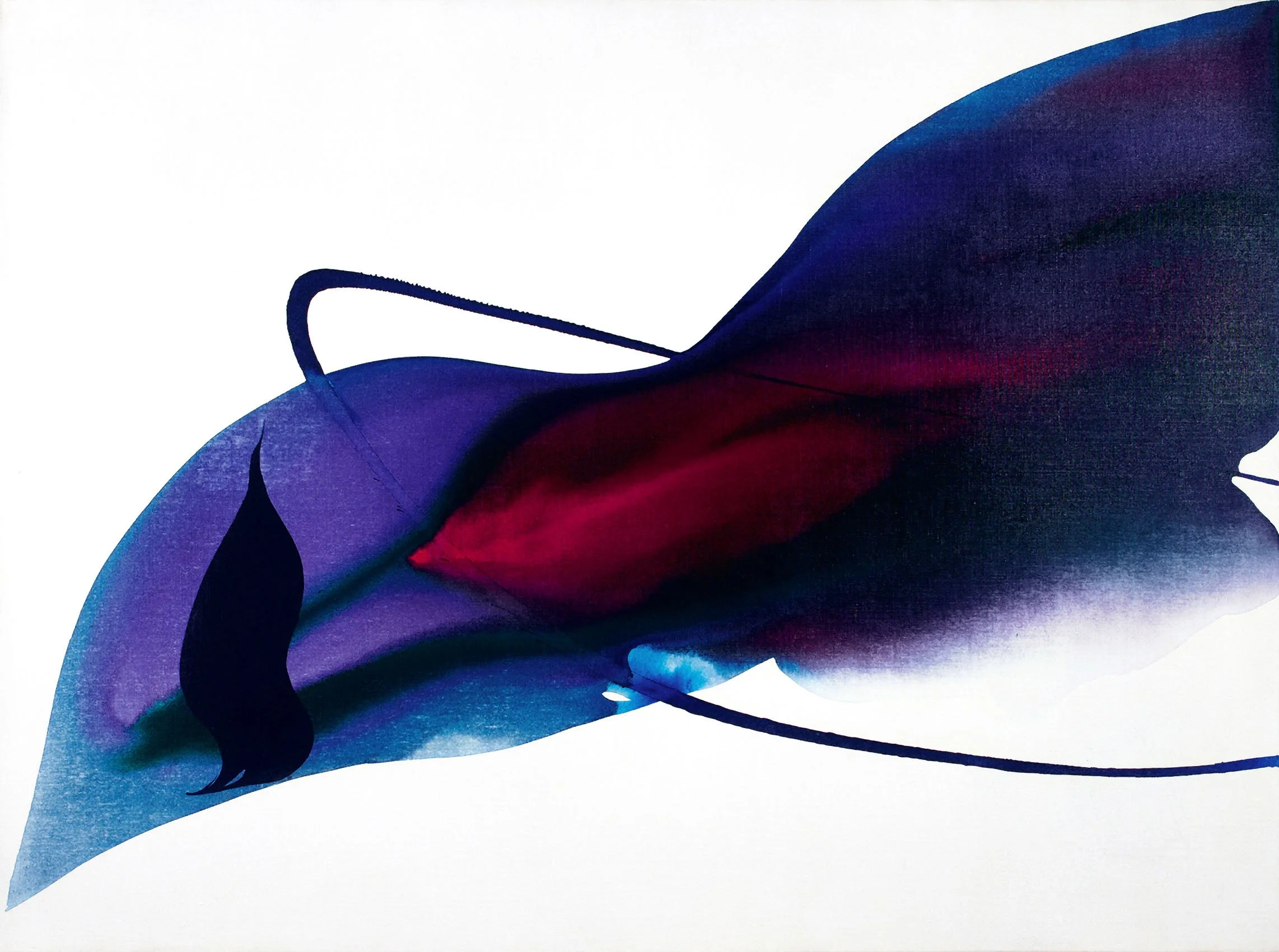

In the first years working in the new acrylic paint, Jenkins had a minimal palette, predominantly red and blue. This can be seen in Phenomena Play of Trance (1962) and Phenomena Wand Passing (1963) in our exhibition where strong calligraphic forms are set off by the white ground. By the mid-1960s Jenkins expanded his palette, loosened his shapes, and the white ground takes a lesser role as seen in Phenomena Violet Contour (1966) and Phenomena Welsh Banner (1967). The use of the ivory knife is evident in the crisp edges of the flowing color and thin lines of denser paint. In the 1970s paintings in our exhibition, one sees an artist who has mastered his craft, working in compositions of all-over color or layered veils in varying densities of paint. In Phenomena Frigate Dawn (1977-1978) Jenkins layered transparent veils of color horizontally in subtle shifts of blue and green and in Phenomena Land in Sight (1978) he used the full spectrum of colors in veils coming from all directions. Some of the paintings have a granular texture to bring attention to the paint surface. Jenkins uses this heavily for a ceramic-like quality in Phenomena Wind Buttress (1977-1978) and lightly like silt in Phenomena Place of Three Rivers (1978).

Paul Jenkins’ career was long and international. His first solo exhibition was in 1954 at Studio Facchetti in Paris, where Jackson Pollock had exhibited two years earlier. This brought further European exhibitions and proceeds from sales allowed Jenkins to set up a studio on rue Decrès. While living in Paris, Jenkins met Mark Tobey, Ellsworth Kelly, and Joan Mitchell. In 1957, Jenkins exchanged his Paris studio for Mitchell’s New York studio at St Marks Place. The dealer Zoe Dusanne in Seattle gave Jenkins his first American solo exhibition in 1955, from which three works were purchased by the Seattle Art Museum. The same year Martha Jackson became his New York dealer. Jenkins had ten solo exhibitions at her gallery over the next 20 years. Jackson’s passionate commitment to artists, both young and mature, and her bold introduction of new experimental works attracted collectors, museum curators, and critics. In her 1956 exhibition Oils by Paul Jenkins, the Whitney Museum purchased Divining Rod. Jenkins also regularly exhibited in Paris (Galerie Karl Flinker), London (Arthur Tooth & Sons then Gimpel & Fils), Los Angeles (Ester Robles Gallery), and Detroit (Gertrude Kasle) throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

In 1964-1965 Martha Jackson’s film production company, Red Parrot Films, Ltd. documented Paul Jenkin at work in his studio. The film, The Ivory Knife, was shown at The Museum of Modern Art and received the Golden Eagle Award at the Venice International Film Festival in 1966. In the early 1960s Jenkins kept a small studio at 537 East 12th Street and in 1963 rented a more spacious, light-filled workspace at 831 Broadway from William de Kooning, where he continued to work until 2000. Jenkins’ Broadway studio became a magnet for artists and dignitaries. Jenkins gave a party for France’s first lady Danielle Mitterrand which was attended by Paloma Picasso, Robert Motherwell, and Berenice Abbott. The 1978 film An Unmarried Woman was filmed in Jenkins’ studio and the actor Alan Bates studied Jenkins’ technique for his character. The Strand bookstore located across the street from 831 Broadway dedicated a window to their old customer in 2012 on the occasion of Paul Jenkins’ death.

[ TOP ]

Modernism 1913-1950 | Realism of the 1930s and 1940s | Abstraction of the 1930s and 1940s | Post-War | Selected Biographies